Transcript

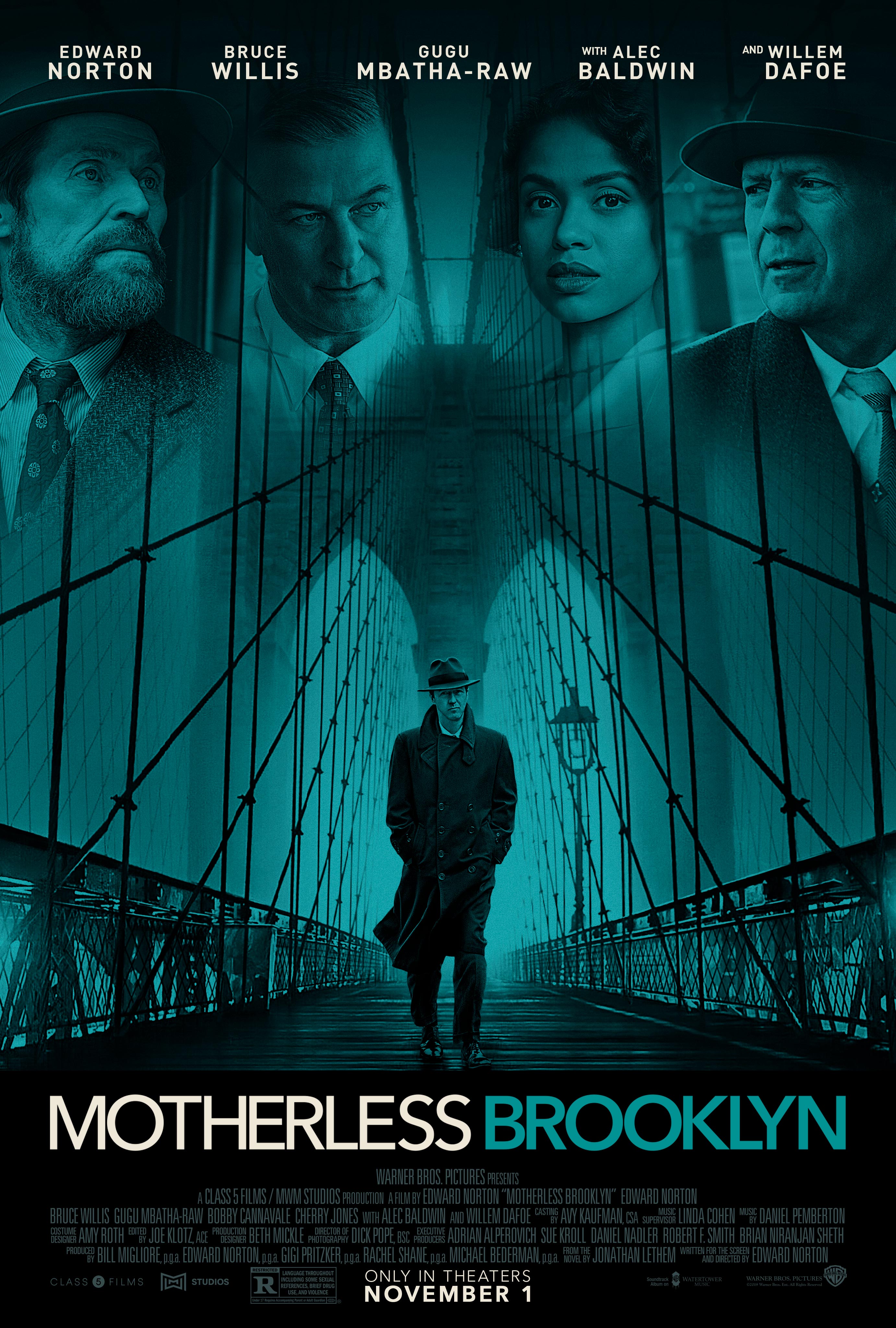

Kaitlin Fontana: You’re listening to On Writing, a podcast from the Writers Guild of America, East. I’m Kaitlin Fontana. In each episode, you’ll hear from writers in film, television, news, and new media discussing everything from pitching to production, from process to favorite lines in jokes, and everything in between. Today, I’m thrilled to welcome Edward Norton, the screenwriter, director, producer, and star of Motherless Brooklyn. The film is an adaptation of Jonathan Lethem’s acclaimed novel. I’m going to talk with Edward about his many screenwriting jobs, how he gets past writer’s block, and his 20-year journey taking Motherless Brooklyn to the big screen.

Hi, Edward. Thanks for being here.

Edward Norton: Great to be here.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah. Congrats on Motherless Brooklyn.

Edward Norton: Thank you. I like coming in to my union, you know?

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Edward Norton: It makes me feel like the cabbie in Clifford Odets’ Waiting for Lefty.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah. Well, I mean, we’re very happy to have you here, and it’s always nice to have people on site and be reminded of the breadth and depth of this union.

Edward Norton: Yes, I agree.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah. This has been a long time coming for you. You have had the rights to Jonathan Lethem’s book since 1999, 2000, somewhere around there, 20 years?

Edward Norton: Yeah, mm-hmm (affirmative). I’m a New Yorker of almost 30 years. I moved here the week after I graduated college in ’91. And in the ’90s, when I was kind of coming up in the theater and starting to work in films, Jonathan was an emerging writer out of Brooklyn, and we knew a lot of the same people.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah.

Edward Norton: We actually had one common friend, and I was aware of his first books. But literally, I remember I was at a party, literally about five blocks from here, and this mutual friend said, “You know, Jonathan’s got this book coming out that’s really special about a Tourettic detective who has to solve the murder of his mentor and only friend,” or something, and I was like, “Wait, stop, what?” I was like, “You had me at Tourettic detective. Like, what?” And I said, “How can I get it?”

Anyway, I chased down Jonathan and I got a copy of the book in galleys on a Xerox, which is-

Kaitlin Fontana: Right on, yeah.

Edward Norton: … yeah, yeah, you know, no PDFs. Yeah. So, I had a clip-bound copy of the book in a Xerox, and I read it and I was completely hooked by the character.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah. Can you tell me a little bit about the journey from that point to the eventual writing of the scripts?

Edward Norton: The initial experience of reading it, I think, for many people is it is not unlike when you read Catcher in the Rye and Holden Caulfield introduces himself to you with an interior monologue.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah.

Edward Norton: Motherless Brooklyn begins with Lionel’s voice inside his head telling you who he is, and what his condition is, and it does what we all try to do as writers writing songs, writing movies, plays, you want to hook. It’s the hook, right? It’s like, “What’s the hook?” The hook in this is immediate emotional intimacy with Lionel. And from there, Jonathan just expands into this glorious, intimate relationship with this character and his unique mind, which is by turns funny and painful and smart and afflicted. It’s just such a hot mess of contradictions and beauty within dysfunction. It’s just this great ride.

And because you’re inside with him, you have an intimacy and an empathy, right? That’s what I really responded to, and it was not even just that I particularly related to the idea of the mind that twists around words and plays and can’t stop on a very deep level, but more that I love things that create an identification with a character, and where it pulls on your empathy. I think consciously and unconsciously, when something makes us root for an underdog, we elevate. You know what I mean? Something good happens inside us. It’s almost like we remember that’s the kind of person we want to be, and I’ve always really responded to those kinds of stories.

And so, this put deep hooks in me right away, and I thought initially, like really, I was more an actor than a writer. I was like, “I really want to think about this character. Taking on this character would be an incredible challenge,” because it’s not just the accuracy of, how do you do that? How do you do those physical compulsions, twitches, ticks, vocal compulsions? What’s the volume? All my brain just started going crazy on, actually, the challenge of representing that condition, and yet finding the humanity, and blah, blah, blah.

But I think we were still shooting Fight Club when I read it, or it was just finished, and I was maybe prepping Keeping the Faith, and I knew I had a long road in front of me of planned work. And so amazingly, I said that to Jonathan, or when we did that deal, we did something fairly unusual, which is, I said to him … Because he had never had a book option at that time.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah.

Edward Norton: And I hadn’t done much optioning, but I knew enough to know that I wanted to marinate on this for a while. And so, we did something kind of unusual, which is I just asked the studio to just buy the rights, completely. No options, no nothing.

Kaitlin Fontana: Wow.

Edward Norton: And at the time, I think for Jonathan, it was kind of like, “Hey, let’s give you a lot more money than what you get in some low-grade option,” you know? But I do want this. I want to be able to do this on my own timeline.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah.

Edward Norton: And in retrospect, I have to say, it was amazing for me, that that was good for him and that we did that way, because I needed the time. I needed the time, and if there had been a constant refrain of pressure and having to reconvince people that I was still going to do it, I could see this whole thing having dissolved into lack of faith that I was still committed to it?

Kaitlin Fontana: Sure, yeah.

Edward Norton: So, I bought myself a long timeline. And I’m not just saying that because I think that that’s on a producorial level or anything like that. I actually really feel, looking back on it, I do think there’s some things that just have to gestate. Some things you know immediately what to do, and some things you know this is going to need gestation, and I want the time for it, you know what I mean? Sometimes, I think it’s really important to allow yourself … We’re in an Instagram and Facebook world. We’re in a world where impulse control in terms of Twitter and all this stuff is literally at an all-time minimum. As writers, I actually think we exist in a world where slow thinking has never been more compressed, you know what I mean?

There’s that great book by Daniel Kahneman, Thinking Fast, Thinking Slow, and I think really good writing needs slow thought. A lot of times it needs slow thought. Not that there aren’t moments of inspiration, but for me, I do a lot of dreaming and thinking and marinating and gestating on a thing. Things puzzle themselves out, and I could never, ever have gotten where I got with this, which was a departure in many ways from the book, I could not have done this on a tight timeline. There’s just no way. And thank God Jonathan not only was amenable to that, as time went on, and I had these bolder ideas, he proved to be just this incredibly confident artist who wasn’t being possessive or precious about his book. He cared about the character, but he didn’t care about the plot, per se.

Kaitlin Fontana: Interesting.

Edward Norton: And that liberated us into sort of the second phase of it.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Well, that’s interesting too, because one of the things I thought about, having been a huge fan of the book as well, and just how Jonathan writes in general, that there’s this sort of separation of church and state, almost, with the actual book, and then this work, which the book takes place in the ’90s. This film takes place in the ’50s, which is a more organic spot for a detective novel, to fit a detective story of any kind, to sit. But it is a departure, like you say, and I’m wondering whether that was something that you teased out sooner in the process, or was it something that you came to realizing what you wanted it to be?

Edward Norton: In 2002, I went through this work that I knew I had to do, and in 2002, I had this really crowded year. I did Red Dragon. I did 25th Hour with Spike Lee and David Benioff, and then I did a play all year. And I finally got to the end of the year, and I was like, “I’m satiated. I couldn’t have a better year, more challenging year, as an actor, and I’m taking a break.”

So I took a break, and that was the year I really cleared my head. I did pilot training for six months just to do something completely different. And then I settled down and was like, “Okay, now I’m going to work on this.”

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah.

Edward Norton: And the thing about Jonathan’s book is that there’s a monolithic quality to the character. He’s so good that I would say most people, if they reflect on the book, what they remember is the character, his mind, and Jonathan’s language, the use of language in the book, this torrent of love of words and language, and the twisting of it. Yeah, there’s this descriptive quality to the way he talks about Brooklyn and the people in it. But most of it is this torrid love affair with language, and film is a more literal experience.

You’re looking at something. Your mind isn’t reading words and inventing a kind of a miasma of imagery, of surreal imagery. It’s film. You have to put something up there. And I wondered and worried, like, “What are we going to do? What is this story about?” The book has a tone. It has kind of a meta surrealism in a way, in the sense that it feels noir. It’s a very clear … It has a love affair with Chandleresque conventions of noir and detectives and tough guys and murky details and all of it, but it’s set in the modern world.

The thing is that Lionel and the guys, these orphans who went to St. Vincent’s and came up in the hard streets of Brooklyn and worked for this PI who’s enigmatic and mysterious, they feel like they’re in some bubble, some time capsule that hasn’t moved from the ’50s. And I really did worry about irony, because I think on the one hand, there’s the Blues Brothers, there’s Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, there’s kind of that thing of like, “Hey, we’re doing retro style in the modern world.”

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah.

Edward Norton: When you do that, it can be a lot of fun, but it is definitely very self-conscious. There’s a wink-wink when you’re doing that, there’s a tongue in cheek. One of the first things I said to Jonathan was, “My instinct was that Lionel’s too good to turn him into a gag. He shouldn’t be a running joke. He shouldn’t be. And his pain, his isolation shouldn’t be in a way softened by irony.” And he responded to that, “I had this notion, before anything to do with Robert Moses or New York history or anything, I just had this kind of impulse that maybe this whole thing just plays better if it’s set in the time that it feels like.”

Because in the book, all his best friends call him Freak Show, and I kept sitting there and thinking, “What is a modern context where you’re buying that, unless, again, you’re being super ironic?” You know what I mean? And the more I thought about it, I just thought, “If we set this in the time that Jonathan’s evoking, as opposed to sort of doing this thing that works in a novel, which is kind of a hypermodern or split between tone and reality, maybe we can play it more straight. Maybe we can be more hard-boiled. The world can be tougher. It can be meaner. He cannot even know what he has, and then his emotional isolation is real.”

It started to appeal to me, this idea, as I thought about it, because Tony Vermonte and Minna, and all these guys, I was like, “These feel like classic noir characters to me,” you know? I started to get excited about the idea of the depth that you could go to with Lionel if you let the world around him be pretty hard-boiled. And I floated that to Jonathan, and he was intrigued by that, but then that was sort of the big obvious question become, “Well, if the book deals with the Yakuza and Zendos and the Japanese sea urchin trade, do we care about that?” At some point Jonathan said to me, “Look, I’m going to be honest. The plot in this is sort of an armature I wanted to hang the character on.”

Kaitlin Fontana: Sure.

Edward Norton: He said … I think he used the phrase, “The plot was an excuse to write the character.” And I enjoy the plot in the book, but it is not about anything per se, and by that I just mean, it’s not the story of his family.

Kaitlin Fontana: Right.

Edward Norton: It’s not the story of New York. It’s not a commentary on anything. It is kind of Byzantine. It’s construct without context, in a way, you know what I mean? It’s almost like you get lost in the maze of it and in part because it isn’t a commentary, you don’t even know what to make of it, you know what I mean?

Kaitlin Fontana: Right, right.

Edward Norton: I started thinking about even the title and the sensation in the book of these orphans, these guys who have had no one looking out for them, and Minna becomes the father they never had in this motherless world, and they lose him. And now they’re truly adult orphans, essentially, and Lionel in particular is dislocated from his family, in essence. He’s now forced to be an adult with no shelter around him, and it’s kind of about him growing up in some sense, and kind of becoming Minna.

I liked this idea. This idea started to creep in my head, “Well, New York in the ’50s, Brooklyn, in fact, was in its own way kind of orphaned.” The old New York got brutalized in that period. I did what you talked about, thinking slow on things. I remember exactly where I was when I kind of woke up in pre-dawn and thought, “Jonathan’s whole idea of Motherless Brooklyn,” literally, the title of the book, I thought, “what if you tried to go ahead and send Lionel into a story literally about how Brooklyn got abused too?” Brooklyn was orphaned, and New York as a whole city suffered the blows of no one looking out for it. I really did get that sensation of like, oh, God, that would be really cool if Lionel … If you could expand up and off of Lionel and all his themes and take what I think is at the heart of Jonathan’s book emotionally, which is empathy and the loneliness of not having people in your life who are caring for you, and externalize that out into a story about the whole city. And lots of things cascaded from that for me.

That’s what I love about Chinatown. Chinatown’s about the personal and the political. It’s, you come away from that with an essential sense of the deep dark story that’s under L.A., right? And when you start thinking about that, about New York, if you know anything, you can go very quickly to what happened to this city in the ’50s and the degree to which we’re literally still dealing with massive problems that are very hard to correct in New York as a function of some very, very dark and anti-democratic and racist things that were done. In the capital of the world, the egalitarian melting pot where everything is supposed to be, this is where democracy works, and actually, we had this incredibly, incredibly dark stretch of history where an autocratic, anti-democratic racist person literally overpowered all of what we think of is the way things are supposed to get done.

I think that’s kind of a hidden history. It’s still a secret history, even with Robert Karrow’s book, even with the New York documentary that deals with him. And I thought that would be kind of cool, the idea of Lionel winding his way into all of that. I floated it to Jonathan, and Jonathan said, he goes, “Man, look, here’s the thing. I wrote my book. You don’t have to rewrite my book. I wrote my book and maybe its like Chandler’s Marlowe, he’s going off into another novel, you know?”

That was in 2003, and that’s when I started getting serious about going, “Okay, now I have to figure out what happens after Minna gets killed, and what is it really all about, and how do we mash up everything emotionally that’s so great about Lionel and his story in this book with a bigger story of literally what happened to Brooklyn itself?” And that took a while.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah, I’m guessing, yeah. I mean, it’s great to hear you kind of go through that process, because I think we don’t often get to hear about that slow thinking model of writing something, you know? We’ve talked to people on the late night side where that’s obviously the complete opposite of slow thinking. It’s, by design, fast thinking.

Edward Norton: Yup.

Kaitlin Fontana: It’s great to think about that slow thinking model in terms of what you are finding as a screenwriter, and being able to, like you say, to give yourself the time to wake up in the night, to work on other projects, to expand your thinking around something. Which also kind of makes me think about you as a writer in general, because I think some people might come to this thinking, “Oh, this is the first time that Edward Norton has ever written a screenplay.” But you’ve been writing in some form or another since your Yale days, perhaps-

Edward Norton: Yeah.

Kaitlin Fontana: … or even after?

Edward Norton: Oh, yeah, sure. I mean, yeah, I have two partners in our production company, but my partner, Stuart, is a writer and director. He wrote Keeping the Faith, which I directed, and he wrote and directed Thanks for Sharing, and The Kids Are All Right. He got nominated for The Kids Are All Right.

Stuart and I went to college together. We lived together in New York in shitty little apartments and we wrote spec scripts for The Simpsons and Seinfeld-

Kaitlin Fontana: Amazing.

Edward Norton: … and we … Honestly, the first money either of us ever made in the entertainment business was we sold a movie we wrote, a comedy, kind of a silly superhero satire kind of thing, and that was literally the first check we ever made-

Kaitlin Fontana: Amazing.

Edward Norton: … for anything creative was for writing a screenplay. And he went on to write for Mad TV and a variety of TV shows, and then wrote Keeping the Faith, and we did that. But we used to write sketch comedy and do it down on Ludlow Street at Nada-

Kaitlin Fontana: Oh, yeah, Nada, yeah.

Edward Norton: … and we were always writing. I did, I mean, I worked with Miloš Forman on the Larry Flynt script, as we worked on that. He was a director who was constantly taking things and breaking them down and finding truth in them that fit his cast. Honestly, he was someone who taught me that a script is not a film, it’s an armature. It’s a frame that lots of other layers of a sculpture have to get built around, and he told me he was a powerful believer that casting, to him, was this linchpin moment where then you had to re-examine the script and basically go …

In his way of working, the script had to mold itself around the kind of almost intrinsic qualities of the people, and he did. I think those guys wrote a hilarious and wonderful script that they were rightly celebrated for, but I also think Miloš went and made it a lot less jokey, a lot less … I remember that script being funny but a lot like their script of Ed Wood. It had a very satirical … Everything ended in a tag.

Kaitlin Fontana: Right.

Edward Norton: I mean, Miloš Forman was one of the great thinkers and dissectors about the protean, anarchistic spirit of individuals pressing against structures and bureaucracies and stuff. And he was taking that one in a very … I don’t want to say serious. That’s not totally fair. There was seriousness within their thinking, but he took a lot of what I would call the farce out of it and took it into a really serious look at the way that principles get challenged by uncomfortable extremes. And we beefed up the legal … The speeches I give in that, those were things I worked on with him.

And then because of the work I’d done with him on that, he told Jim Brooks that I’d helped him a lot on that, and so when Jim was working on a movie that was originally called Old Friends and it turned into As Good as It Gets. I spent some time with Jim working on that one, the summer after we did that. This was coming in and doing character punch-up work, and brainstorming and rewriting things and stuff, and it was almost like getting used as a brainstorming partner for other people on scripts.

But down the road, I worked with David McKenna a lot on the American History X script, and I worked with Stuart on the Keeping the Faith script and stuff. And somewhere after that period, I started really doing it more formally. I took rewrite gigs. For money, I did studio punch-up gigs on the score, and other things, and I wrote a new version of that script, Frida, for Salma when we were trying to put that together and worked through that whole production on that script with Salma and Julie Taymore.

I did that kind of stuff a lot. I took studio work on the Hulk and on all these things, but a lot of these things, to me, it was sort of like, “I’m going to do this quasi as a job, and quasi because I just want something I’m going to be working on to go to the next level, but I’m not going to do it …” I’ve already caught so much frigging nonsense flak for this, for getting involved. You almost want to say to people, “Wait, I’m not getting … showing up with notes or …” That’s one thing, getting hired by a studio for four weeks at a weekly to do a pass. That’s not like an actor inserting himself. That’s getting hired as a writer.

Kaitlin Fontana: Right.

Edward Norton: I’m working as a writer, getting paid. And it’s impossible in this click-bait world to dissect the nuances of these things for people, but everyone I’ve ever been involved with these things, we all just sort of shake our heads. It betrays a lack of understanding of the way things actually work.

But quietly, I was doing lots of work as a writer, and sometimes even on movies I wasn’t involved in. I took a couple of gigs just doing rewrite, punch-up work on things. And that was good for me. I did it also in part because I found it challenging and I found it interesting to try to service, figure out even on genre stuff, what’s the mechanism here?

On The Score, Miloš’ theory applied when, I think, it was Mandalay brought me in to work on that before we made it, and it was like it had shifted from being kind of a caper movie to being Brando and De Niro and me, and it needed a total overhaul to write for us, because we weren’t going to do some caper version of it. We were going to do the us version of it, and I tried to make that more of an analogy to the three of us as actors, almost, generations of people. And it was a lot of fun. It was a lot of fun working on that.

But those, for me, that kind of work, doing all that kind of work was helpful because it wasn’t slow thinking per se, but it was a great way to kind of polish my own sense of just building the musculature of working in a screenplay configuration, and figuring out how to discipline myself within the necessary limitations of the length of a movie or whatever.

Kaitlin Fontana: Sure.

Edward Norton: And I think it helped me. It helped me get to a place where I felt by the time I wanted to do something like this, I wasn’t having to get a tutorial on how to use final draft, you know what I mean? I’m serious.

Kaitlin Fontana: Right. Yeah, yeah, yeah. No, sure.

Edward Norton: It was like it felt fluid to me. I had spent years and years and years doing it in kind of what I’d call low stakes configuration.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah, yeah. Well, and I wanted to bring that up because I think it’s important to, as a writer and as a member of this guild, to kind of remind people that there isn’t this separation between the actors and the writers. A lot of people move through these worlds fluidly, and just because we see you in a certain sense doesn’t mean you haven’t been doing the work in the background the whole time as well.

Edward Norton: Absolutely. When I sat down to do this, I felt really clear about the first third of it. I wrote the first third of it really in a kind of a blitz, and then I got really hung up. It’s like, to me, really good noir films, they take you down into the murk. In almost all of the good ones, you really don’t know what’s going on, and in fact, I would say it’s not even convoluted is a given, but actually committing to the idea that an audience is going to get lost, actually lost. In Chinatown, I would say it violates every norm of Robert McKee’s screenwriting-

Kaitlin Fontana: Totally.

Edward Norton: … no matter what anyone says. Anybody who says they know what’s going on in that movie until the last 20 minutes is lying.

Kaitlin Fontana: Definitely, yeah.

Edward Norton: You have no idea what’s going on in that movie, really.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah, yeah.

Edward Norton: That is Polanski’s magic trick of hypnosis. Music and image and Nicholson and the clothes, and you’re just like, “I don’t know what the hell is going on here,” and it is moving at a pace that has nothing to do with what people normally say needs to happen.

Kaitlin Fontana: Right.

Edward Norton: Motivation. What’s his motivation? He has no motivation in the movie. Someone tricks him in the beginning by hiring him and pretending to be someone else, and he doesn’t like it for his reputation. There’s no emotional … He has no abiding emotional motivation for doing anything in that movie, and to me, it’s what makes it truly great noir, because the noir detective is us. It’s an American sensibility of, like, “Hey, I’m just doing my job. I trust the system. I’m not a crusader. I’m not a moralist.”

But something starts to irritate him, remember?

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Curiosity.

Edward Norton: He actually … Curiosity, but also all he really says in that movie is, to her, he says … She says, “Leave it alone.” You know, Evelyn Mulwray basically says to him, “Thank you. I will pay you to stop.”

Kaitlin Fontana: Right.

Edward Norton: And he goes, “See, the thing is, someone put one over on me, and that’s not super good for my reputation. I don’t like it.” It’s literally just kind of American gene that says, “Someone’s playing me and I don’t like it,” and the further he knows he’s into it, the more irritated he gets, until he’s with Noah Cross, and he’s like, “How much is enough? How much do you need before you stop screwing the rest of us? And why are you doing this?” And the answer isn’t good enough for him, and now he’s pissed off, you know what I mean?

And I think that film works on such subconscious levels. It does not trace. And by the way, when he thinks he knows what’s going on, 20 minutes before the end, he’s wrong about everything, you know? It’s not at all what he thinks it is. I think I believe in that. I don’t believe in the … I think critics radically underestimate audiences all the time. I think no audiences want to get ahead of a movie. Very few want to be right with it. We love to not know what the hell is going on, but to have a conviction that something grown up and sophisticated is happening, that’s holding us in it. I got to this point where I was like, I got lost, too lost, in the murk of my own thing.

Kaitlin Fontana: Sure.

Edward Norton: And I couldn’t crack it, and then I got an offer to do a really interesting film. And then I put it in a drawer, which was, that’s a lethal decision, because once I put it in the drawer, then it was like, “Oh, we’re doing The Illusionist in Prague for six months.” It’s like, “Wow, that sounds like a lot more fun than taking that out of the drawer and trying to figure it out.” And then it was like, “Okay, I’m going to do it in the second half of the year.” And then it was like, “Well, we finally got the money together to make The Painted Veil,” which we’d been working on for seven years.

Kaitlin Fontana: Right.

Edward Norton: And it’s like, “Oh, we can go to China and make the film we’ve been wanting to make with Naomi Watts.” It’s like, “Well, okay, so I’m going to work on this next year.” And then it’s just like writer’s block combined with other compelling opportunities does not produce the motivation to sit down and do the hard work. Ultimately, I put it in the drawer for a couple of years, which poor Jonathan probably … He said he had a multiplex in his mind, and it was a multiplex that was playing all of the books that he’d written that had been options that had never been made into movies.

He was like, “There’s the movie, there’s Motherless Brooklyn, The Fortress of Solitude,” all these things, and I felt really bad. Ultimately, I got goaded. A smart studio executive, I think, kind of quasi, maybe he was lying, maybe it was real, but he told me, like, “Another director is really interested in this, and maybe we should let him take a crack at it.” And I was kind of like, “No, no, no, no, no, I got it,” and that motivated me and I got it back out.

Then two of my really good friends, who were Writers Guild East, Brian Koppelman and David Levien, they had written Rounders, created the show Billions. We had done The Illusionist together. They produced that. And I kind of said, “I need help. I need to literally bring you guys in. I need to put all my cards up and show you where I’m blocked and tell me what I’m missing,” you know what I mean? And I used them as like my logic sounding board.

It was amazing. It was like with distance and time, things that had seemed really like a knot that I couldn’t untangle got much more clear, and I remember David Levien saying, “Wait, but you just said, ‘That works.’ What’s wrong with that?” And I was like, “Wait, but does it?” And I remember him saying, “I think you already have it. You’re not seeing it.” It was just, a little bit of third party perspective on the whole thing, and suddenly I was kind of through this knot, and then I was able to finish it.

Kaitlin Fontana: It’s funny how that happens. I’m a big believer in the walking cure of you’re-

Edward Norton: Walking and talking?

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah, yeah, yeah, like you’re lost in something and then you go for a walk, and you come back and suddenly this thing that’s been intractable for hours or weeks or months is suddenly solvable-

Edward Norton: Sometimes I-

Kaitlin Fontana: … because you just broke the chain of thinking a little bit?

Edward Norton: Sleep. Sleep does that for me a lot. I find that things percolate up in sleep, sometimes in that period right before you wake up, or you’re waking up and you’re thinking, but you haven’t really moved. I find that particular period very productive for that kind of thinking.

But I thought you meant walking. I always loved when I used to read about Woody Allen that he would, with writing partners, he would just walk in the park, walking and talking it with a writing partner and scribbling, and stuff like that, and then going home and pounding it out. And I’ve seen Wes, you know Wes Anderson and Roman Coppola and Jason Schwartzman? I’m with them all the time. Sometimes we take vacations or whatever, and they go off and do these sessions where the three of them, they just walk around and they gab about Isle of Dogs, Moonrise Kingdom, or whatever. And then Wes goes away, and takes those sessions. I love that. I think it might be almost like a primate thing, like we’re a social animal, and so there’s something about language and speaking it that sometimes it can unlock it.

My other partner, Bill, when I was starting to groove on this, we would go out to … You know the Hamptons in the winter? Another writer friend of mine, Ann Biderman, who created Ray Donovan most recently, but is a great screenwriter. She wrote Primal Fear. Has always been kind of a writing mentor to me, or whatever. She had this little house out on the island. We used to go up. Bill and I would walk around in the cold, talking about Motherless Brooklyn, and trying to think through details of it.

I wish this one had gone faster, in some ways, but in a weird way, I think the other benefit of going slow with it was that things were going on in the culture around us. Not even just our current politics, which have made it much more resonant in some ways, by emphasizing that everything stays the same in some ways. I mean, there was aspects of what’s gone on with the whole Me Too, the comeuppance, the exposing of these dark psychologies of the way that powerful people metastasized the ugliness of their power into private psychosexual dimensions of their life. And literally, that coming up in the culture opened up layers in this to me that were there, but I wanted to underline more in some sense.

So, having time on it also gave it more of an opportunity to develop into something I always think is great, which is if something … It’s like Joseph Campbell’s line about transparency, “If you can see through a story, and see how it’s about you or about the moment that you’re living in, it activates.” It activates in a very different way. Your mind activates and it stops being a passive interaction with a story that’s downloading itself to you with all of its conclusions or whatever, and it becomes more of an activated response because the mind starts grasping the analogies or grasping the resonance. And then you start having a dialogue even as you’re watching the thing, almost like you start filing things and that’s what you end up talking about at dinner, do you know what I mean?

Kaitlin Fontana: Right, right, right. Yeah. Well, let’s dig into that, because I think one of the things that was so interesting as a New Yorker and just looking at the history of the city and the story, even though it is in the ’50s, it feels right now, in part because of this Robert Moses/Jane Jacobs pairing of characters that are not called that in the film, obviously, but are these analogs of these figures, and to me that was very resonant. I’m glad you brought up Me Too.

There’s something very specifically masculine and feminine about those energies that happen to be embodied by a man and a woman, but I think the energies that they bring are so different, and I really liked how the film played with the sort of masculine Robert Moses captive industry-

Edward Norton: Bruce Willis, Bobby Cannavale, yeah.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah, there’s that whole side, and then there’s this feminine energy brought to light by Cherry Jones’ character, and Gugu’s character that is more about community and building something together in tenderness.

Edward Norton: No, I’m glad … It’s funny, I have not had the room and time to really discuss that dimension of it, but I think that’s really true. I’d even, in a funny way, I’d say that Willem Dafoe’s character, Paul, is on the feminine side of it too-

Kaitlin Fontana: Absolutely, yeah.

Edward Norton: … in the sense that he’s the one who’s also saying things like, “To serve people you have to love people,” you know? He’s invoking the idea of the care, care for other people. And I do think the longer I worked on this, the more I felt amazingly like we are, we’re in a national conversation again. I tried to weave this into the script that there have been phases in American life where, in the Depression, and in the New Deal, where literally, we defined American heroism, literally. FDR and the New Deal and the passionate sense of uniting that was taking place in the country, it was about digging ourselves out of pain by taking care of each other. Literally, the whole country rallied around the idea. The Workers’ Progress Administration, the Civilian Conservation Corps, we were doing things to help each other get back on our feet, literally.

And after the war, America’s currency changed a lot. Suddenly, we were a superpower, and suddenly, power became a value and an aspirational goal and a function of what Eisenhower called the military-industrial complex, and we started using words like superpower. And arguably, we started conferring, or ascribing, a kind of a heroic value to our strength.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah.

Edward Norton: And to me, across that period of the ’50s, but still today, there’s definitely this argument, in a way, between are we … Who do we want to be?

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah.

Edward Norton: I saw Cory Booker saying, literally, last time on The Daily Show, “Do we want to actually define our character as strong because we care for each other, or strong in a muscular, exclusionary …” There’s no other way to say it but the bully, that sense of the me and only me, not us, not yes, we can, but I am the solution, on my authority, on my power, and winning, and all these types of things. What you have down underneath it is really, it is in a deep sense, it is the masculine and the feminine in some sense, or it’s the idea of strength and achievement versus nurturing and revitalizing, caring for, et cetera.

I think of, I like the idea that Lionel is so enmeshed in his … Lionel’s condition defines his life. It’s got a very narrow or small footprint, because the only place he is cared for or functions is under Minna’s wing.

Kaitlin Fontana: Right.

Edward Norton: But when that’s gone, he’s sort of set loose and adrift in this world. Again, not a moralist, not a crusader, but more like a person who now has to become an adult on his own terms. And I really liked the idea that the story he sets off in ends up presenting him with choices. It’s like, Alec Baldwin’s character and Bobby Cannavale’s character, they literally make him sincere offers in the film to join them in the decision to get what you deserve, to be a part of the visionary progress that includes people saying, like as Alec says, “I’m not going to stop the great work of the world because a bunch of chipmunks are nattering about having to relocate their nuts.” Except he’s talking about people and communities, but he’s saying to Lionel, “There’s a place for you here, because I see your talent.”

And on the flip side, he’s got Laura, Gugu’s character, Cherry Jones’ character, Willem Dafoe’s character, saying, “What is happening here is not okay. Human beings are getting destroyed, rolled communities, we’re experiencing losses, and this is happening.” I like the idea that until the very end, he hasn’t decided what he’s going to do, or what or who he wants to be, and I think that that’s one of those weird things. You sit and think, “That’s not what Jonathan wrote his book about per se,” but literally, the title of the book is Motherless Brooklyn. It is this idea of people and places being orphaned and the consequences of it, and I really love that and I love the idea that you could go wider with that, even, and still stay true to the source material, because I think that adaptation’s a really funny idea, in some sense.

We were at Telluride and Jonathan said … Someone asked him, like, “Were you freaked out or offended or whatever?” He was like, “No. I can name the movies that I think are pretty terrible because they stuck with this stuffy fealty to the source material, and it just didn’t work as a film,” and then he was like, “I can name the movies I think are genius because they springboard off of a thing and become something in their own right.” And I think, “Thank goodness he had that attitude.”

But I do think if you look at things, like a film I think really holds up, Out of Africa, because Sydney Pollack, I think, is one of the great directors, and Meryl Streep’s one of the greatest actresses of all time. And when you watch that film, still today, you realize it works because it’s not just because it’s beautiful, it’s because it has a really timeless theme in it of impermanence. It’s a woman trying to possess and hold onto things and having to constantly come to grips with that she’s going to lose everything. Everything will be impermanent, but that her life and her spirit are in experiences, not in the idea that you can hold on to anything.

It’s beautiful because it is universal and timeless and eternal. But when you look at that, I think Dinesen never wrote a book called Out of Africa that comes even close to having the narrative of that romance between her and Denys Finch Hatton and the events. The entirety of that film is a narrative construct that’s created completely up and off of Out of Africa and Shadows in the Grass. Out of Africa and Shadows in the Grass are essentially like memoirs with very little narrative structure in them, but what they have is a heart tone. They have an evocative sense of memory and of detail of little details of life. And they took that, and then what they knew about her and her life and everything, and they created, not a false, I think … It’s not certain whether she indeed had an affair with that particular person.

Whatever, they created something that had a much bigger narrative scope than anything that was in those two very slim memoirs. And yet, when I’ve read those books many times, that film is so true to the heart of her sensibility, you know what I mean? And I think sometimes you’ve got to liberate yourself, not even just liberate yourself, challenge yourself to imagine the ways that film can do some things that you can’t do in a book.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yes.

Edward Norton: Because otherwise, you’re not making a film.

Kaitlin Fontana: Right, right. Yeah. I think it’s interesting. That’s where I think the genre becomes a really interesting part of this puzzle, the detective genre, because there was this great piece that Ken Burns wrote about the film-

Edward Norton: Yeah, it was-

Kaitlin Fontana: … where he talked about, he saw it at Telluride, he loved it. He wrote about it. I really liked, if I can quote a little bit of it to you: “The film seizes back the moral core of film noir, liberating it from easy despair, and in that process, reinjects a nearly obsolete genre with power and purpose and profundity.” What I like about that, aside from obviously, it’s a very nice compliment to you from a fellow filmmaker-

Edward Norton: Yeah, no, his essay put me flat on my back. It was really incredible because I admire Ken enormously. I think he’s one of the great American storytellers, not just filmmakers. I think he’s taken complex history and made it so emotionally compelling.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah, yeah. I agree, and I think one of the things that’s so nice about him saying that is that it would be easy to just say, “Oh, the detective story is sort of like the thing that all of this other stuff hangs on,” but I think it’s completely intrinsical to how this story comes through that character and he’s not … That way, it was, to me, less Chinatown, where as you say, Jake Gittes is sort of like apolitical about the whole thing. To me, it reminded me a little more of The Long Goodbye, where there’s more of an emotional investment, and also the character has a cat, and I was like, “That feels like a Long Goodbye reference.”

Edward Norton: Yup.

Kaitlin Fontana: But it feels like there’s a moral core that this character’s trying to get back.

Edward Norton: Well, I think that Maureen Dowd, The New York Times’ columnist, amazingly just wrote a couple weeks ago, this essay about Chinatown, comparing it to the current modern political landscape. And she highlights, she hits dead on, I mean, dead on what I’ve always felt about that film, which is, that is a film made as Vietnam is collapsing and Watergate is exploding, and the filmmaker’s wife has been murdered at eight months’ pregnant. That film basically says, “You never know what’s actually going on, and when you try to contend with the people who really have power, you will,” this is what he says, “you’ll try to keep someone from getting hurt, and they’ll get hurt in the worst way.” And the conclusion is, you should do as little as possible.

Kaitlin Fontana: Right.

Edward Norton: Literally, that is the last line of the film, “Do as little as possible. Do as little as possible.” What? Come on, Jake. It’s Chinatown. You know what I mean? It is as existentially bleak a conclusion as you could imagine.

Kaitlin Fontana: Right.

Edward Norton: But I don’t think I like what Ken wrote. Tony Kushner said a really nice and similar thing to me, which is, he told me he was kind of worn out almost on the cynicism of noir. And I think you can have all the health and vitality of noir’s insistence that we look at what’s going on in the shadows and that if we don’t we’re in danger, you know what I mean, Without necessarily concluding that apathy is the right response, you know what I mean, to those dangers.

But it’s funny, because you say, “Well, if I had rushed and done this 20 years ago, I guarantee you, I would have had a 30-year-old’s …” I would have thought it was cooler to stick with the cynicism of the genre, and as a 50 year old with children and the world we’re in, I don’t think there’s any room and time for that right now. I honestly, my own value system is so different and my sense of the world is so different, that it didn’t seem like a responsible option to me to say, “Yeah, in the end, say, ‘I don’t give a shit what happens, just leave her alone so that I can be happy,'” you know what I mean? Which is where you could have gone with it, but it’s not just where I wanted to go. And I don’t think it’s less noir because of that. I think it’s, like you say, I think there are precedents for more of an insistence that there can be morality, you know what I mean, That there can be activism or participation in the world. There can be a determination to do something heroic within it.

The other thing that I think’s kind of always a choice with things like this is, that I think Chinatown gets right, I think Citizen Kane gets right, is at a certain point, you have to say, “Am I doing a history, or am I doing literature?” You know what I mean? Some people have said to me, “Well, why didn’t you just call it Robert Moses?” And it’s like, “Well, because it’s not Robert Moses.” This has a murder and it has deep psychosexual histories and assaults and rapes and illegitimate children and all kinds of things, and those things don’t have anything to do with Robert Moses.

Kaitlin Fontana: Right.

Edward Norton: Indeed, many other details of it are a melange of things that other powerful people did. And you have to say to yourself, I think, “Well, do I really want to sit around and have to account for what’s not true when I’ve used the names of real people?” You know what I mean?

Kaitlin Fontana: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Edward Norton: I think it’s very interesting, because E. L. Doctorow, or there are people who wrote fictions in which true historical characters are present. And it can work, but on the flip side, if you’re going to ever say anything’s based in truth, you better get it really right. I have a real beef with people who take wild liberties with a story that you’re saying is true, you know what I mean? And to me, in this case, it was just much, much, much more sensible to say, “I want to infuse this with a lot that will not line up with history.” It’s also fundamentally based on the novel and the character from a novel. There isn’t a deeper truth conveyed if you say this is like a weave between fictional characters and real characters, it’s like it just gets confusing.

Kaitlin Fontana: Sure.

Edward Norton: And to me, Charles Foster Kane, it might have been William Randolph Hearst in large measure, but it wasn’t William Randolph Hearst. It’s documented what the other people and things and elements of people’s scandals that they wove into that. There’s a whole trace of the melange of things that Welles and Mankiewicz worked into that character portrait. And that way, too, it’s not this time-stamped document. It’s this thing that it became. It’s this epic commentary on the America character. It’s a literary character, not William Randolph Hearst.

Kaitlin Fontana: Right.

Edward Norton: And Hearst has faded into oblivion, but Charles Foster Kane remains this iconic representation of America’s drive and excess, you know what I mean? And it stands on its own feet. I think generally speaking, I lean really strongly towards staying off of the declaration that something’s based in truth, unless …

One of the things I loved about Foxcatcher was just how diligent it was. I mean, it’s a brilliant film. It had something to say, but they just didn’t screw around with ultimately a very … Because those events are so wild and those are real people’s stories, and it’s like you can’t create fake redemption around stuff, you know what I mean? I think it’s really funny, because I remember … Akiva Goldsman’s a really good friend of mine, and he’s a great writer, but I remember how tripped up they got with Beautiful Mind on just details, like the fact that John Nash was gay, or that he and his wife ended up separating, and she was still at the Nobel ceremony.

You know, when you can understand when you’re working in studio land, and things, “Oh, well, could we get rid of this?” Or, “Could you make it more,” this and that. Who knows what drives decisions, but when I look back on something like that I go, “Look how much friction this terrific film, this terrific film, great performance, very evocative underdog character, showing, reminding us these things.” I mean, the amount of noise they had to deal with around these details, you know, it just to me is sort of like, “Nah, let’s just-”

Kaitlin Fontana: Stay away, make it about Lionel, and-

Edward Norton: Yeah, yeah. Let’s let this exist as allegory and essential truths, instead of … Because to me, if people walk out of it and they go, “How much of that really happened?” That’s where you want people, if they’re in an inquisitive space, if they’re in a thing of going, “Was there really someone like that? That can’t be true. They didn’t really lower the overpasses to prevent minorities from getting speeches on buses.” And then, if it means it makes them go look, then that’s perfect, you know what I mean?

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah. You’ve opened the door.

Edward Norton: Yeah.

Kaitlin Fontana: Well, Edward, thank you so much for coming here today and being part of the podcast.

Edward Norton: Yeah, pleasure.

Kaitlin Fontana: It was a pleasure to talk to you. Feel free to drop by your union any time.

Edward Norton: Yes. I’m a fan of the union.

Kaitlin Fontana: Thank you. That’s it for this episode. On Writing is a production of the Writers Guild of America, East. Tech production and original music is by Stock Boy Creative. You can learn more about the Writers Guild of America, East online at wgaeast.org. You can follow the guild on social media @wgaest, and you can follow me on Twitter @kaitlinfontana.

If you like this podcast, please subscribe and rate us. Thanks for tuning in. Write on.