Marina Fang: It struck me that this film has a lot of processes that sometimes have to be explained to the audience, and sometimes there can be a risk of having too much of dialogue serving as exposition or introducing a person when … or the audience needs to know who the person is. But sometimes it’s unnatural for someone to be like, this is so and so. But sometimes you kind of just have to do it so that the audience knows. How did you figure out that balance of when you need something to be explained through dialogue and when there’s another way to do that visually, or if it was just sort of unnatural to do that?

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: Well, some of the time you just dive in with information. So, visiting Schmidt with the accounts and just talking about payments with a wife next to him, you know what I mean, that really happened. But you just dive in and you hope that people will join the dots because there’s not too many dots to join. Sometimes it was about getting information over. And for instance, I thought it was incredibly important that NDAs were obviously a huge part of the story and the system that enabled Weinstein. And Jodi and Megan were investigating NDAs generally alongside to see where their strengths or weaknesses lay.

And they saw that none of the law schools were studying NDAs. So, it’s almost like these nondisclosure agreements are kind of under the table. They’re just there and they’re so gagging and binding. And law students don’t even study them. And I thought that was incredible. So, that’s just a tiny bit of information, but how do you get that on screen? And in the end, it was kind of like a bundle of quite excited, well, I wouldn’t say excited because they’re more professional than that. But a bundle of enthusiastic information from Megan and Jodi feeding back on what they found. And you do think, oh, that’s a lot of words and a lot of information, but that these actresses can make it animated and great.

Marina Fang: And it makes sense. I think what it’s a journalism movie, of course, a lot of the work of journalists involves updating your editor kind of where you are in the story. And that kind of lends itself naturally to having those scenes where they have to explain what’s going on, and therefore that helps also the audience to know what’s going on.

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: Yeah, absolutely. And at one point, Rebecca Corbett and Matt Purdy talking to Megan, and we wanted to make it the second half of the conversation more personal about the baby. And Matt gets a phone call and goes out, it’s kind of like, use a device. It’s very simple, oh, have to go. And suddenly the conversation changes gear a little. So, these things are very simple. But it’s just structuring something so that, I think originally that was two scenes. But we thought, let’s make it into one scene and see what happens. So, there was a more female scene, and then there was a more just about work scene. And then we thought, well, we can just mix the two, but evicted Matt at some point with a phone call.

Marina Fang: Are there other tricks or maybe not tricks or techniques that are helpful that where just having a character leave the room or something like that, that kind of helps break things up a bit? Or just finding ways to make something visually more interesting?

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: Well, again, I think it’s about rhythm and also how much information we can withhold. You give people a break from information for a while so that the information coming later is exciting, don’t overload each scene. You might have a very vocal scene. And then I would err towards a non dialog scene after that so that we are processing as we are watching the next scene. I think scenes where people are alone are very interesting. So, with this, I was very much interested in the public face of the journalists and then the private face. And that’s throughout the film too, just private moments of people, Jodi waking up in bed with a phone call and a slight light on her face. I think it’s very interesting when things feel very private and you literally are looking into someone’s private life. I think that’s interesting.

Marina Fang: Yeah, I think one of those, I guess, sort of combines the public and the private, but I really liked that a lot of the film is built around the conversations that Jodi and Megan had with all of the sources. And for me as a journalist, I felt like it was important because it gives the viewer a window into what it’s like to get people to come forward and how hard that is and how hard it is to then sit with them as they tell you something very difficult or something that they’re not allowed to say. Or whatever it is. Including those in pretty great detail, what did you want to capture about those conversations?

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: Well, it was hard to capture them. And what we have on film is not an accurate portrayal because for instance, if Jodi was finally talking to a survivor, she wouldn’t just dive into tell me about it, how was it, what happened. It was a very gradual and sensitive series of conversations. So, what we show on screen, for instance, with Laura Madden is after a lot of buildup, a lot of preparation. And so Jodi would say, can I ask you this question? Can I ask you that question? You can say, I don’t want to answer it, but here’s a question, here’s a question.

And it was very sort of building up a relationship and a conversation incrementally. But I suppose Filmically quite hard to do. So, we did take a liberty there in saying, okay, here was this conversation and here was this conversation. And what we show is a summation of all those different conversations, which were delicately built up. So, it was months of work put into, here I am at the restaurant, tell me what you’ve got. And so that is inaccurate, but I felt that it’s in the spirit of what they did and that it would’ve been kind of nigh impossible to show each kind of inching towards phone call.

Marina Fang: Yeah.

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: Perhaps it could have worked, but the rhythm felt like you want to meet the person and have a whole conversation.

Marina Fang: And a lot of that is, like you said, it’s emails, it’s phone calls, it’s a lot of time.

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: But it’s very gradual, as you know, with journalism. It’s gradual. So, it is a more brash telling, but I couldn’t see a different way of doing it.

Marina Fang: Yeah. Was there ever a point where the producers wanted to do this as a miniseries at all?

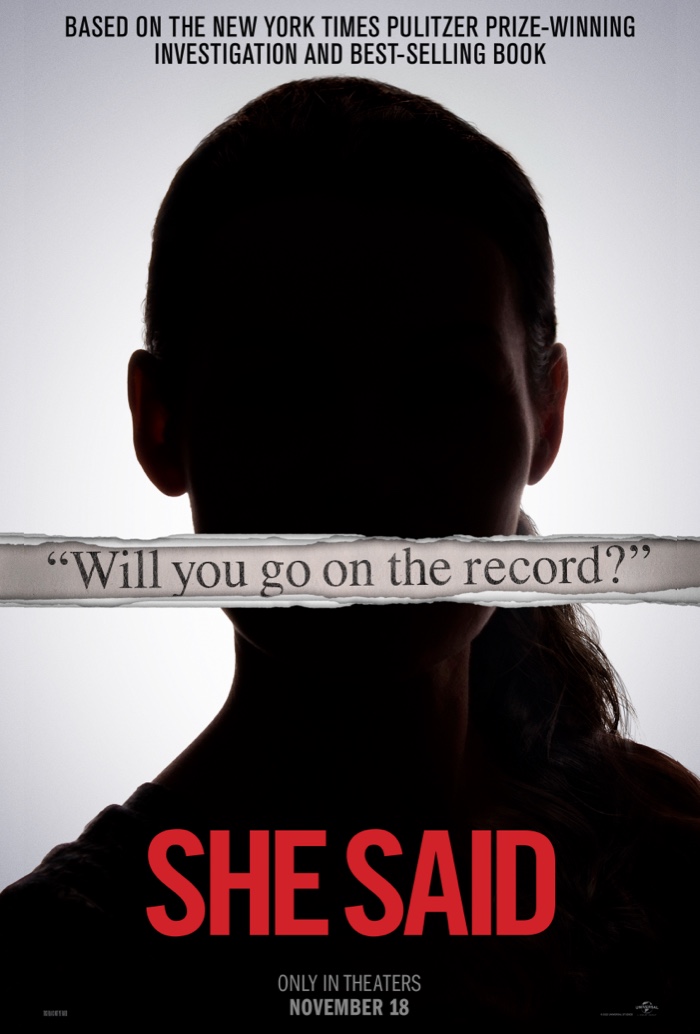

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: They didn’t talk about it, but there would absolutely be enough material for a miniseries. Yeah. There was so much detail and it would work very well in seven hours or however many hours. But the producers, they produce Moonlight, 12 Years a Slave. They love making films and I love making films. And there’s something very satisfying about seeing the arc of this story just go from nobody knows to at the end push the button and everyone knows. So, there’s something about the volition of it in a two hours, eight minutes, which is incredibly inviting as opposed to, and next week. I think it’s rather healing to see the whole thing and to let out the emotion. Because I do think it’s an uplifting film. It’s about a collective of women who changed events, changed systems. They kind of reignited a huge amount of interest in Tara Burke’s Me Too movement. They’ve changed the way things work in Hollywood. It’s not fixed, but there are changes. It’s seismic what happened, it’s historic. So, I think it’s rather satisfying to see it in one complete telling.

Marina Fang: Yeah, definitely. Of course, I couldn’t help but think about some of the other journalism movies throughout history, and I’m wondering if you drew from any of those, or did you try not to. Did to think about them? Or were there certain elements that you didn’t want to try to recreate or replicate?

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: Well, I saw Spotlight when it came out and was very moved by it and the journalism in it was brilliant. But what I also remembered was the survivors. I remembered where they were when they were telling their story. I remember their faces. I thought that they were depicted with such honesty and respect. So, I wanted to honor the witnesses and the survivors who had contributed so hugely to the investigation. And then I rewatched Spotlight sometime into the writing and thought, yes, it’s incredibly strong and brilliant. And then there were whisperings of, oh, this is a female, all the president’s men. And I’d seen that years ago and really enjoyed it.

But after finishing draft, after draft, I did rewatch it, just to see are there parallels. And I don’t think they’re very similar films. I think it’s a brilliant film, and it’s the only film that William Goldman said, I wish that had never happened to me. He had a terrible time on it. But it’s a beautiful depiction of journalism. But they’re all very different films. But I think that, especially at the moment with such fake news and journalists being really fighting for their lives in many ways, I do think it’s important to show brilliant investigative journalism and how much it contributes to society. It’s very impressive. So, that was important to get it right.

Marina Fang: Yeah, definitely. I wanted to back up a bit and talk about your career more broadly. I know you originally trained as an actor and did some acting for a couple years. Why did you make the shift into writing? And then how did you start to find your footing as a playwright?

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: Well, I wrote a play before I was an actor.

Marina Fang: Oh.

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: Yeah, because I was going through some sort of depression and doing this crazy CD job, and I wrote about it. I kind of wrote it out of my system and it became a comedy. And I thought that was interesting that from tragedy there came comedy. And that was in my early 20s. And then I trained to be an actor for three years and acted for seven years, and absolutely loved acting. But I wasn’t hugely successful. I either did great parts in fringe or tiny parts at the national or the RSC. So, there was a lot of temping. And with the temping I was writing to keep myself sane at night.

I would write, and I loved the writing. And then the writing got busier and I gave up the acting. But I never regretted the acting. I loved it and made brilliant friends who are still my friends and also had that feeling of being part of something, which is less so in writing because a lot of it is quite solitary. But that feeling of being part of a company is wonderful. And as well as the huge hard work, there’s a lot of fun. And I admire actors hugely. I think they’re on the front line in terms of making anything. And I think it helped with the writing, just having said words, it was a good training for writing. Yeah.

Marina Fang: Yeah. I was going to ask you that. That was my follow up, was how does the acting experience kind of inform the writing?

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: Well, hugely, because first of all, you realize how difficult acting is and that you can’t just point to actors and say, do this, do that. That there is such a process, deeply complex process to create a role. And to be honest, on stage is so hard, and your job is to give the actor as much help and ballast with that as possible so that it’s not about what you want to say, it’s about what the character needs to say. So, it’s interesting. It’s very interesting.

Marina Fang: Yeah. And then how did you start writing for the screen? And I guess before that, was there ever any interest in adapting your plays for the screen, either from just on your part or from producers?

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: Yeah, there was some interest. But it didn’t, like I did a play about the suffragettes. There was a lesbian love story in the middle of it that was the center of it. And they said, we want to make a film, but as long as you make it a straight love story. So, I said, let’s not do that. And I was writing plays for a decade before I was writing screen and loving writing plays. I mean, hard work, but brilliant. And then I kind of crossed over Kristin Scott Thomas wanted to make a film and she asked me to adapt a book. So, I did that. And from that, I just started putting my toe and foot into screenplays. And then I met [inaudible 00:39:26] and we met at a party and ended up, I ended up co-writing either with him. Although he already had a script of it and he didn’t like the script. And so we started again on that. So, it was quite an organic way into film.

Marina Fang: What are some skills that, from playwriting, that translated to screenwriting? And then the flip side of that, what was sort the learning curve or things you had to learn as you were getting into screenwriting?

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: The hierarchies are quite different because in playwriting, everyone is very conscious if they want to change punctuation, let alone a word. So, you get used to a lot of questions in theater about why you’ve written it this way, why you’ve written it that way. And there are similarities. But I would say that film, of course, is a series of dances. You write the screenplay, then the director sees what they want to do with it, and then the act to see what they want to do with it. It’s kind of more a series of processes. And with a play, if you’ve written a play, you might have four weeks to rehearse it and put it on. So, you’re in it together, you change the ending, you see a preview, see if it works.

Actors give you feedback and say, can I say this? It’s very sort of live as it should be. Whereas the writing of a film can go on for a decade. And draft and draft and draft. So, they’re just very different processes. But I do think that essentially you’re always after interesting psychology and interesting stories and surprises. They are very different mediums, but I think that it’s very possible to cross from one into the other. Just the same with acting isn’t this huge division anymore between theater acting and film acting, it’s basically about telling the truth. It’s just how you size it in a theater and as opposed to in front of a camera.

Marina Fang: Yeah. How do you compare, I know you’ve also done TV as well, and then in a couple of TV writers rooms, looking at theater versus film versus TV. Is there one that you kind of prefer over the other, or are they just hard to compare?

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: I don’t prefer one over the other, but I do think it’s great if you can combine them because they are very different experiences. And so I think in terms of finding sanity, it can be really satisfying to mix them.

Marina Fang: Speaking of TV, I wanted to ask a little bit about that. Because I know a lot of people listening to this podcast probably have done sort of like you said, a mix of all three. What did you learn from TV? And also, I guess from being in a writer’s room, and I feel like that’s sort of its own experience compared to being a playwright. Being a screenwriter, when mostly it’s you rewriting the script or maybe with a collaborator.

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: I’ve done a lot more theater and film than television. I’ve had a little bit of experience in TV, but I’ve had nothing on TV compared to the films and plays that I’ve had produced. So, I know writers who just adore TV, but it hasn’t really happened for me in that way. The writer’s room, the one writer’s room I was in, was absolutely fantastic, brilliant writers. And it was wonderful feeling of collaboration and stories and very generous atmosphere. But actually having television on screen, it hasn’t really, I’m doing a few projects at the moment, which hopefully might happen. But I’ve had the sat quite a lot, so that’s me on telly.

Marina Fang: Has your approach to writing shifted or changed as you’ve worked in these different mediums, or, I don’t know if you feel differently about it or if your perspective has changed a bit?

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: I had an important phone call today with Nina Steiger at the National Theater about a play. And I said to her, it’s strange, the more you write in some ways, the more vulnerable you feel. You’d think it would be different that you feel stronger and stronger, but it’s almost like the act of doing another play and another film, it is like a boxing ring. It’s a fantastically enjoyable process, but you have to be very tough and at the same time, very fragile to let ideas in and to let things happen. So, it’s an odd mix. And I do find that you don’t get more robust. Your craft is more and more honed, and you feel like you could do certain things standing on your head, and that’s great. But your don’t become a pachyderm in terms of being criticized or wanting to be liked. It’s all still very, very complex. And every day I think a mixture of, I can do this and can I do this. So, it’s interesting. It’s a very interesting life, but I don’t think it’s what anyone imagines a writer’s life is.

Marina Fang: Yeah. What did you imagine a writer’s life would be, and how is it compared as you’ve actually done it for so many years?

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: I don’t think I had too much time to imagine what it would be like, because I kind of went straight in and I still derive an incredible amount of joy from it. But I think other people perceive it as a life of incredible freedom and inspiration and romantic. And I wouldn’t put romantic at the top of the list of what it feels like to be a writer or glamorous.

Marina Fang: Yeah. Do you feel like you have more power now as a writer having done so many things, and especially now that you’ve had a lot of screenwriting under your belt, do you feel like you can kind of say yes or no to different things?

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: Oh, absolutely. Yeah. I feel like I have a voice in the industry and that’s good. And I can say no to anything. That’s something. And I feel responsible for making things, for putting women in the center. I feel that it’s not something to toy with that as you get older, there is, it’s not like you have to wave a flag. But with a voice comes responsibility. And so you choose your stories more carefully in terms of what impact they will have, especially with, well all medium, but more people will see films than they will see plays. So, you want to know that for instance, She Said, I hope that a lot of young women will see it and feel solidarity and that they’re shoulder to shoulder with any other young women who having a negative experience. Things like that, you feel part of your tribe and that you should be attending to that.

Marina Fang: Yeah. What makes, you answered this a bit, but what kind of makes you say yes to something and as you’re considering whether it’s a screenplay or a play, and also just figuring out the balance of the work that you do?

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: I think more and more it’s about the people you work with. So, it’s absolutely the subject matter. Do I want to write that? But I would never write something now unless I felt I had the right conditions to express myself. So, it’s about working with people who you feel you really are excited by, and who give you the right conditions to be writing in, which is freedom.

Marina Fang: Yeah. You mentioned you have a couple other projects coming up. Is there anything that you, I’m sure some of them are things you maybe can’t talk about. But what are some things that you can talk about that you want to talk about?

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: Well, the call today was about a play for the national theater, possibly. But an incredible Indian female spy in the Second World War. And that’s a story that has been with me for a long time and started as a screenplay and didn’t get made. So, I have made it into a play and hoped that it will be on. So, it is quite interesting how things come out in the end about a woman called, Noor Inayat Khan. And she kind of won’t leave my body until I have put her somewhere, which is interesting because you do get an emotional relationship with the people you write. Differently if you are writing real people like Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey, you still feel emotionally involved with them, but you realize these are real people. But if you’re taking someone from the past who’s dead and you are kind of resurrecting them, you sort of become them for a little while. And couple of TV series that are exciting and a couple of films that might happen. So, yeah, all really interesting projects.

Marina Fang: Yeah. You feel like we’re at a good place to wrap. I guess, was there anything else that you wanted to say that I didn’t ask about or anything that you just felt like it was important to get across?

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: No, I think you’ve done a brilliant job of asking everything that’s in my head. Is there anything that you feel …

Marina Fang: I had a few other questions, but I also just felt, I felt like this was a good ending point, talking about where you are right now and just your big broad approach to how you choose what to write about and what to dedicate your time to as a writer.

Rebecca Lenkiewicz: Yeah, yeah, yeah. I think in my 20s I wrote about my own dysfunctional love life, and then there was more of that in my 30s. And then since then, I think politics has come more into the fore, just in terms of being female. That’s a political act, and I do think that film is such an incredible medium for getting information out to people. It’s so powerful and we must use it well. Yeah.

Speaker 1: On Writing is a production of The Writer’s Guild of America East. This series was created and is produced by Jason Gordon. Our associate producer and designer is Molly Beer. Tech production and original music by Taylor Bradshaw and Stock Boy Creative. You can learn more about the writer Guild of America East online at wgaeast.org. You can follow the Guild on all social media platforms at WGA East. If you like this podcast, please subscribe and rate us. Thank you for listening. And write on.