Noah Baumbach: Well, once, there becomes a kind of, this is true, even I think of an original script, I mean, I don’t know if you feel this way. But when I’m writing an original script, I’m working off of notes and scene lists and things that I’ve collected and put into a document. And then, as I start writing, I’m often trying to work in things either that I already have or I’m ideas I have for what I think I’m doing. And then, there becomes a point where it really transforms and it starts to take on its own life and starts to tell you what it is. And not that it’s always that clear in telling you. But it’s like the characters start to have more kind of emotional logic to them and you start to say, well, this person wouldn’t do that, so I can’t do this scene now because this wouldn’t happen.

And I felt that in adaptation too, that in the beginning, it was kind of like to more look at the trying to get the novel into a way that I felt would work as a movie narratively. And then, at a certain, point it starts to become its own thing and its own movie. So then, things get cut and things get moved around and I start writing my own version of things. Because I feel like the movie needs that and I’m not thinking about the book anymore or certainly not in terms of any kind of loyalty to the book. And I feel like that that’s when things start to work better is when you feel that kind of freedom.

Alison Herman: Sure. I mean, the body of DeLillo adaptations, cosmopolis accepted is obviously not very large and I think there’s a reputation that follows his work as being somewhat unfilmable or at least hard to adapt. I’m wondering if that was daunting or exciting or just challenging for you as you started to wrap your head around taking on this project?

Noah Baumbach: I didn’t think about it. I mean, I was drawn to adapt this book and that’s what I went ahead and did. The notion of unfilmable only was something I really came across once I started doing press for it. So to me, it felt like it could make a compelling movie.

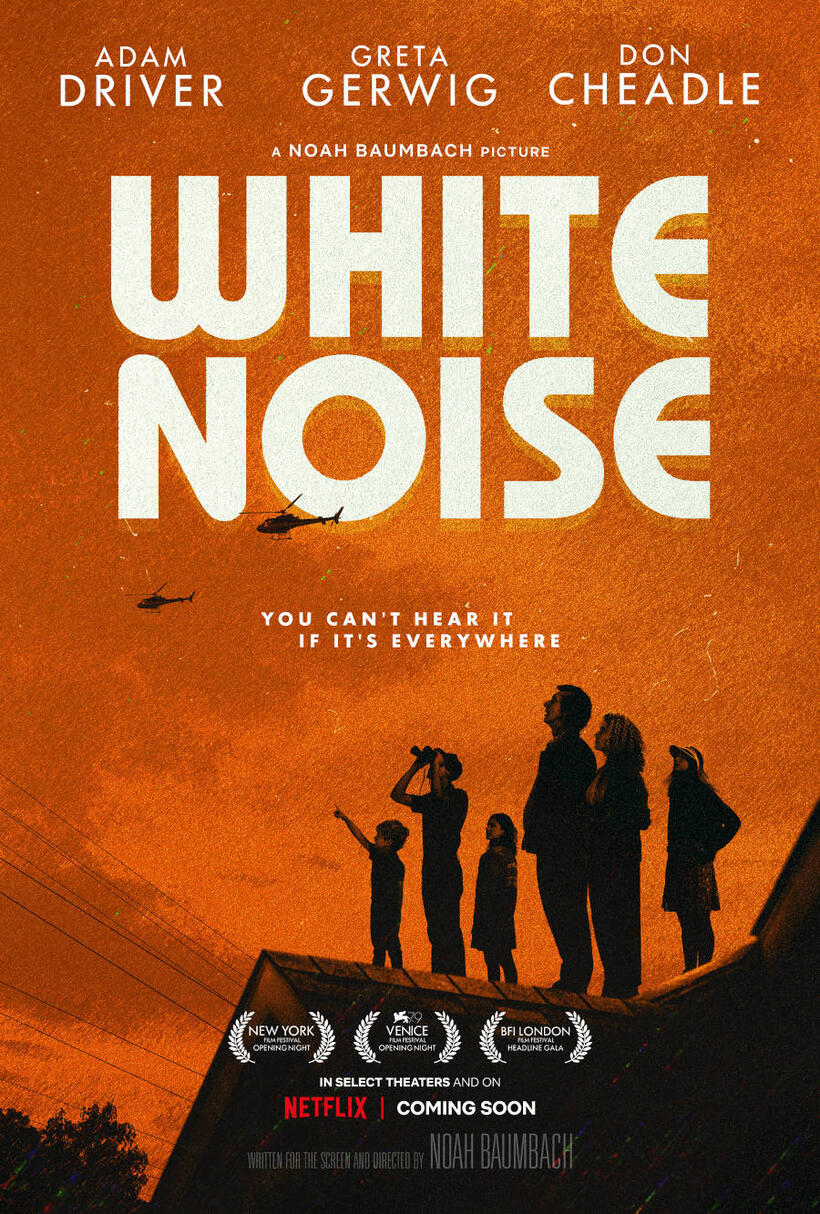

Alison Herman: Sure. Both Adam Driver and Greta Gerwig are actors you’ve collaborated with before and in Greta’s case, not just as an actress. But I was wondering how you factor in actors or acting while you’re writing. Do you ever consult with actors while you’re writing a role that’s potentially for them? Do you envision them in the role while you’re writing? How does that element of the collaboration work for you?

Noah Baumbach: Yeah, I mean, that’s a good question. I factored in a lot. I mean, over the last, I don’t know, maybe since Greenberg or something. I’ve always looked to people that I wanted to work with or I’ve already worked with, I want to work with again. And tended to reach out to them in the early stages to let them know that this is something I’m thinking about. And so, that I start a kind of dialogue with them as well while I’m writing. So I think it also helped in this case with the adaptation because I could think of it as Adam and Greta playing these parts that already helped take it out of the novel for me and change it from the Jack and Babette that are in the novel. I like it very much.

I find Adam and Greta read the book, we talked a lot about it. So as I’m writing, sometimes I’ll reach out to the actors and ask them questions or things that, I mean, in Marriage Story, I did this a lot also because of the themes, the divorce, that’s the center of it. Actors, Scarlet, Laura, who I was working with had also gone through divorces. So we were kind of sharing our experiences and some of those things, found their ways into the movie. Meyerowitz with Adam and Ben and Dustin’s, similarly.

Alison Herman: In the case of Adam Driver, I mean, it’s almost hard to say he has a type since he’s obviously a tremendously versatile and gifted performer, but to the extent that he does academic almost feels like playing against type a little bit. So I’m curious, what made you think of him specifically for the role of Jack Gladney?

Noah Baumbach: Well, I mean, really, the answer is because I like working with him so much, I think he can do anything. But when we first talked about it, we both wanted to tread sort of lightly and slowly in terms of committing him because I think we both felt like, well, the character’s older than Adam. As you say, it’s not written in a way that you would necessarily think of Adam. But I was interested in how, going back to this sort of notion of performance where Adam putting on weight and maybe raising his hairline a little bit and playing more of a part in it could be interesting.

And similarly for Greta, with things like and Don, things like wigs, which I usually would immediately rule out in the case of this movie felt right. It felt like makeup and hair and all these things that it did add this sort of element of disguise to everyone, which I thought was right for the movie. Whereas, in a movie like Marriage Story, for Adam was about playing it as close to the bone as possible. But that said, once they’re in their parts and in their wardrobe and wigs and everything. Also, they play these things quite honestly and truthfully and I think the movie has a lot of real emotional stuff in it. And so, and that case wasn’t particularly different from other things I’ve done.

Alison Herman: Sure. This may be slightly off topic for the purposes of this podcast, but I suppose songwriting is a form of writing. The movie concludes obviously with a new track from LCD Soundsystem. Their first in several years, and I wanted to know both how that came about, but if you had any conversations with James Murphy or anyone else in the band about what the song would actually feel and sound like?

Noah Baumbach: Yeah, absolutely. Well, James and I have been friends since I reached out to him on Greenberg. I was listening to Sound of Silver while I was writing, so I reached out to him and then he wrote music for that movie and then, we sort of stayed friends and become quite close. So he and I were talking while I was shooting and I wanted him to sort of, I didn’t expect him necessarily to write a whole new song by the time we shot it, but I wanted him to work on a tempo and think about a style. And the two big things we talked about were sort of like, well, if your band was making music in 1985, which in some ways it already feels like they are, but to think of those sounds? And also to write a kind of joyful song about death.

And James is always great with the kind of happy, sad thing. And so, that’s why I thought of him particularly for that. And then, when we worked, James and I, David Neumann was with me in Ohio. James was in New York, but we all spoke on the phone and talked about it and he looked at some of the rehearsal footage that David was doing of the supermarket dance. And so, we shot it to a temp beat and then, James wrote the song in post. But it was quite collaborative in that way. But at the same time, I was thrilled and when I heard actually what he was doing, because there’s no way to predict.

Alison Herman: Of course. We tend to ask on this podcast some more generalist questions of screenwriters and how their process works. So just in general, what are your writing habits? When do you tend to write, where do you tend to write, how fast, how slow, etc?

Noah Baumbach: Well, I guess, I find when I’m sort of writing all the time in a way in that I’m always taking notes and always writing as I’m sure you experienced as you can sit in front of the computer and feel like you get nothing done. And then, you walk to your next appointment and suddenly you have a rush of ideas. And so, the question is, when did the writing get done? Was it when you were at the computer or was it when you were speaking into your phone while you were trying to make the light? And I don’t know is the answer. But I find when I have a thing I’m thinking about or something that would qualify, if somebody said, “What are you doing?” And I’m saying, “I’m writing a new script.” I start to see at least an aspect of the world in the context of that story and those characters so that everything seems possible material for the thing I’m writing.

And so, I collect stuff and then I sit down and write. And sometimes it goes fast, and sometimes it goes slow. I mean, when I write dialogue, it often moves faster, but it doesn’t mean it’s all going to remain. It’s often a way to write myself into something. In terms of screenwriting, I guess, things I’ve been asked before. I mean, I don’t outline or do cards or anything like that. It’s more casual maybe than that. But I take a lot of notes and then, I kind of dump them into the script and start to write.

Alison Herman: Yeah, I mean, you now have a career that spans over 25 years of feature filmmaking. So has your process changed or adjusted at all over time?

Noah Baumbach: Yeah, I’m sure it has. But it doesn’t often get easier. I mean, they’re all different. They really are. And they all seem like magic when they’re done. You look back at the last one and you’re like, “How did I get there?” And the odd occasion I look at an old draft or notes of something or I’ll find notes that I wrote about a movie that’s two movies ago or something. And I think, “Oh, wow, that’s right. I had that whole idea of that whole thing.” And none of that is in the movie. I really try to remain as open to the mystery of each one. I mean, that sounds more wise than I actually am. Because really, when I sit down, I feel like this’ll never happen. I’ll never figure this out. But to try to embrace that and be open with it. I mean, some scripts I come into and I have more, I think figure it out in advance. And other ones I’m kind of groping around in the dark and it takes longer.

Alison Herman: As someone who does largely direct your own scripts, do you feel like directing and writing are separate rules for you? Or do they feel like they bleed into each other? And if so, how do they interact in your head?

Noah Baumbach: Yeah, that’s a good question. I think the more I do this, I do see them as all part of the same thing. What I do find is important in the writing stage is to try to maintain that freedom as a writer and not look at it quite yet as a director. Particularly the early stages of a script, is to be as open as possible to who these people are and what the story is and sort of to your thing about White Noise. In terms of the bigger set pieces, I wasn’t really thinking of it. I was thinking of it visually. I was thinking of it as set pieces. I was thinking of it as a movie, but I wasn’t thinking of it from the practical nature of it as a director of how am I going to do this? Which, of course, the director part of me felt very frustrated with later.

So I do like to try to maintain that openness and be a writer when I’m writing. But I do very much see it as part of is as a kind of link to how I’m going to interpret it later. And that I’m writing very much for myself to interpret it. And in subsequently editing, I look at it the same way. I really try to look at it, and I like to also involve the creative. I mean, to what you were asking before about it, bringing in actors. I also like to bring in cinematographer, production designer, costume designer people, anyone who I know I’m working with on this particular movie, an editor particularly, to bring them in the script stage and see what we can accomplish in the script before we get to the movie part where we suddenly have a clock on it and we’re spending more money.

Alison Herman: In addition to your solo writing and directing efforts, you’ve also done a few collaborations with the likes of Wes Anderson and Greta Gerwig. How has that process worked for you and what do you get out of it or how do you approach it that’s different from your more standalone work?

Noah Baumbach: I mean, I love collaborating. It’s sort of different material to me. Different ideas seem to ask for different circumstances. It’s something, I guess, it’s more in intuitive, but there are some things where I felt like, “Oh, I’d like to write this with somebody rather than write it myself.” And then, there are other things that feel more just, I don’t know, more, at least initially private in that way. And that I feel like I’m the one to do this alone. I don’t know why, but writing with Greta has been… I mean, we have a few official collaborations, but she’s sort of a part of everything that I’ve even written on my own. I’m always showing her stuff and getting her feedback and stealing lines from her if I can.

And subsequently, I work the same way with her on things that she’s done. But I always learn something. You learn something working with other people, it’s like it becomes this third thing when you’re working with someone else at its best, I think. It’s like I say something, she says something that makes it better, or she says something, I say something and then suddenly we have this other thing. And that’s sort of a pleasure in collaboration.

Alison Herman: Yeah, we’re approaching, I believe, the end of our allotted time together. But as a final question, I did want to ask about one specific upcoming collaboration between you and Greta, which is, you obviously work together on the script for the Barbie movie, which is to the outside eye, obviously, well outside I think both of your phonographies, but I’m just very curious. No spoilers, of course, but just how you approached that and what that was like for you.

Noah Baumbach: Yeah, well, we wrote Barbie sort of right after, I mean, I was still sort of rewriting White Noise. But after I had a draft of White Noise, we started writing Barbie. And this was all in the sort of, I suppose, what we would think of as the thick of the pandemic in terms of lockdown. And I think both of them benefited from a certain kind of insanity. And so, Barbie was a very freeing experience and really fun. And we made each other laugh a lot. And I think when you see it, I think it will feel more inside both of our phonographies than you might guess anyway. But that was very much that. So what I was describing that feeling of…

But what was different about it was that Greta was going to, I mean, actually Greta wasn’t sure she was going to direct it at first, and then we were liking so much what we were doing and that I felt jealous because I was like, “This is going to be great.” But we were thinking of it much more as sort of not as something. I wasn’t thinking of it as something as I was going to interpret, which in itself creates a kind of freedom too. And in a way a good exercise probably for me. Something else is to think, well, what if I’m not doing this? What would I do? And it gets you outside your own head. But I was really proud of what we accomplished.

Alison Herman: Did you find yourself transposing your DeLillo voice onto the Barbie material? I feel like that’s a hard 180.

Noah Baumbach: Well, it was a good way to write myself out of my DeLillo voice, but they’re more companion pieces. I mean, Greta and I probably will see this more than anybody else will, but they’re not thematically totally different and they also are, but for us, actually, they felt like companion.

Alison Herman: Well, I’m excited to see the movie and I’m excited for everyone listening to this to see White Noise. But Noah, thank you so much for joining us today.

Noah Baumbach: Yo, thank you. I enjoyed it.

Speaker 1: OnWriting is a production of The Writers Guild of America, East. This series was created and is produced by Jason Gordon. Our associate producer and designer is Molly Beer. Tech production and original music by Taylor Bradshaw and Stockboy Creative. You can learn more about the Writers Guild of America, East online at wgaeast.org. You can follow the guild on all social media platforms at WGA East. If you like this podcast, please subscribe and rate us. Thank you for listening and right on.