Transcript

Kaitlin Fontana: You’re listening to OnWriting, a podcast from The Writers Guild of America, East. I’m Kaitlin Fontana. In each episode, you’ll hear from writers in film, television, news, and new media discussing everything from pitching to production, from process to favorite lines and jokes, and everything in between.

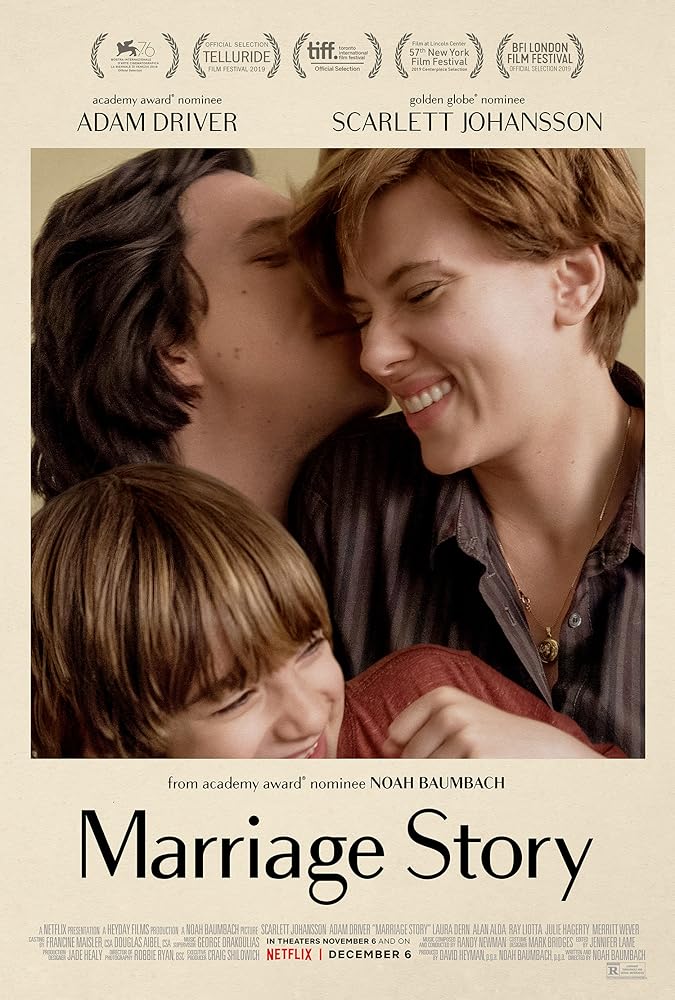

Today, we’re speaking with Noah Baumbach, writer and director of Marriage Story, now streaming on Netflix. Noah made his feature film debut with 1995’s Kicking and Screaming and has gone on to write and direct such films as Frances Ha, The Meyerowitz Stories, and The Squid and the Whale. The script for which was nominated for a Writers Guild Award and an Oscar. We’ll discuss how a film about divorce is really a film about love, what New York and LA mean on screen, and when you know you’re ready to open that final draft file and really write.

Hi, Noah. Thanks for being here.

Noah Baumbach: Thanks for having me.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah, and congratulations on the Golden Globes nominations.

Noah Baumbach: Thank you.

Kaitlin Fontana: That’s a big deal.

Noah Baumbach: Yeah, it’s exciting.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah. Are you surprised at how this film has been resonating with people?

Noah Baumbach: Well, that’s a good question. I suppose I go into all the movies with the same open-hearted feeling of hoping to make something that is going to connect with people. It’s been great that so many people have connected to the movie, and I’ve been traveling with it now since end of August in Venice, and it’s hard to talk about a movie, I find, sometimes because part of the reason you make it is because that’s the way you know how to communicate these feelings and thoughts and ideas. So then, of course, you then have to put it into words, and it can be challenging, and what’s been really helpful to me in edifying, and gratifying, is people have very personal reactions to the movie.

So, I get the movie reflected back to me in talking to people about it, and I’ve learned about the movie, and I’ve learned, actually in many ways, how to talk about the movie from other people. Down even to the point of someone will say something really interesting and I’ll think, “Is it okay if I steal that and use it in interviews?” Because it is, sometimes revelatory to me to hear someone else’s response.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah, I think maybe we don’t think about it when we’re writing something. We don’t think about the dimensions. Maybe no matter how many times you’ve been through a press process,, or something like that, you might not think about, oh, there’s the pitch at the beginning, there’s the film, and then there’s the re-pitch afterwards of bringing it to audiences and repurposing what you’ve already done and put in a drawer in a certain sense.

Noah Baumbach: Right, right. Often people say, “What was the idea for this?” And I often, what I want to say is something like a version of what I said earlier which is, “This was the only way I could express these feelings and thoughts.” And so, I was always interested in other people’s processes, and I think some people have, maybe have a very direct, sometimes very direct, idea but for me it often is many different things. They can be things, it could be a of dialogue, it could be a location, it could be a color of some article of clothing, or just a moment from life, and all of those things help me make story and ultimately a movie.

Kaitlin Fontana: Right. Did you set out to make a film that is, to me, about the day to day processes of divorcing? Did you set out with that in mind or was it more… Because it could be, “Here’s the story of a divorce.” But this is very minuet to. It’s, sometimes it’s moment by moment even. Is that what you wanted to do from the get?

Noah Baumbach: Well, it’s, as you pointed out, it is absolutely the moment to moment of divorce, but it’s also the moment to moment of life. The opening of the movie is little moments from life and observations about these two different people, and part of what I discovered in the writing process was that these little moments aren’t going to go away just because you go through a divorce. And so, the divorce process, and the legal process, is so all consuming, but at the same time, regular life doesn’t know that. It’s still happening, and so you’re still a parent, you’re still the human being on the planet going through your day. You still need your hair cut, you still have to eat, you have to order lunch. So, while the little moments, as you point out, become about the process you’re in, which is the divorce process, but then they’re almost like what’s living side by side that are all the little moments that we go through anyway.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah, I went to a morning screening which was disastrous for my emotional state for the rest of the day, and I walked out about 12:30 or something onto Park Avenue and people are just walking around and shopping and doing things, and I just stopped and I was like, “Doesn’t everyone know that a marriage has ended? What’s wrong with everyone?” And of course that’s, on one level, it’s a fictional marriage, first of all, but it’s also one marriage and marriages end all the time. But there’s something really interesting about how it strikes you when you watch it, that you don’t even realize it sneaks up on you cumulatively, as it were, this epic intimacy, which is sort of related to what you were just saying about there’s this bigger thing that’s happening, but then there’s these little intimate things happening in between. And I found myself so like, wrenched by that, like “Why isn’t everyone stopping what they’re doing and observing the fact that this marriage is ended?” Like, “Why isn’t there a minute of silence happening for this marriage?” And I wonder how cognizant you were of that balance as you were writing it?

Noah Baumbach: I was going to say, first I’ll do the thing that I was talking about before and ask you if I can borrow “epic intimacy”, for when I talk about… Because that’s a great way to describe it.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yes, I’ll take 10% every time you say it.

Noah Baumbach: Sell that. Yeah, there’ll be a little “cha-ching.”

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah.

Noah Baumbach: Well, I think it was a discovery in the script, was this epic intimacy, I’m using it already, was that if I stayed on that track, in a sense, narratively many things could take care of themselves in a sense, because I did, in early drafts of the script, I wrote scenes that went outside that. There were scenes with friends who, other couples, who had been friends, and the scenes get the kid at school and dealing with the school, and all things that were… There was nothing wrong with the scenes themselves, but when I looked at my first draft, or something, which is probably pretty thick, those were the things that immediately, when I was reading it through, announced themselves as things that needed to go because it didn’t stay in this sort of intimate, ordinary realm.

The opening of the movie is, in essence, about how ordinary things in a certain context are extraordinary, and of course, for us in our individual lives, they are, and when you’re in love and you’re pointing out things about someone you love, they take on other significance too. So, that also helped me, as I was writing the script, I had that basis and that introduction, in essence of the ordinary, they were built into those montages.

Kaitlin Fontana: Right. So, one informed the other as you were writing you’d say?

Noah Baumbach: Yes, but at the same time, I’m also always trying to tell the story and sometimes it’s the little things that help create story, and other times it’s story that allows for those other things to exist, if that makes sense. But I find in the sense, if this storytelling is clear and working, those other things start to reveal themselves. They sort of come out of the cracks in some way, and some of them I might notice while writing, and others of them, I’ll find out later. Even after I’ve made the movies, somebody might say something about something and I’ll think, “I didn’t even realize that.”

On my movie, Greenberg, a few years ago I was in the… I don’t know, I was doing my 30th interview, or something, and the person interviewing me said, “I love how you set up what the whole movie’s about in the beginning.” Because it’s Greta Gerwig’s characters driving, and she’s trying to merge lanes and she says, aloud, in the car, as if to the car next but of course the person in the car can’t hear you, but this thing, we all talk to ourselves when we’re driving, she says, “Are you going to let me in?” As she’s merging, and as he said this to me, I started to cry because I realized that that was the case, but I thought she was just merging lanes and got an idea. But the movie, in essence, is about characters wondering… Her asking a character, “Are you going to let me in?” And I knew it and didn’t know it, but I do feel like, because I somehow got some other things right, it allowed for that line to resonate like that and be more profound than it ever consciously was.

Kaitlin Fontana: That your subconscious was in a dialogue with yourself while you were writing and you didn’t know.

Noah Baumbach: Right, and I think, of course, that’s always happening, and I think there’s always going to be a certain amount of those things that remain mysterious, but it’s the other stuff that you can control that allows for them to come out, in a sense, and I think it should remain that way. There’s no way to know about all of them, and I don’t think I want to know about all of them.

Kaitlin Fontana: Right, yeah. Well, there’s, you mentioned this a couple of times already and similarly, there’s this lovely, I would call it, epistolary elements that opens the film, the framing, of these letters that they write to each other about the things they like about each other. And as that’s un-spooling for you, you as an audience don’t know why we’re hearing it until we do know why we’re hearing it, and I won’t say anything in case anyone hasn’t seen it yet because it’s a lovely reveal, and then that kind of comes back full circle as the movie continues. I wonder how soon into the writing process you came upon that element, how quickly that was part of what you were doing when you were writing?

Noah Baumbach: I don’t remember particularly, but fairly soon because I’d never had another beginning to the movie. The movie always began that way. I think, as best as I can remember, I think those sequences actually came from, almost as an exercise. I was going to write… Because I always knew the marriage was going to start at the end, and… The story was going to start at the end of the marriage, I should say, and it was almost like getting a running start into that story, for me as a writer, to understand place, and the family, and what was the day-to-day, and what will be absent as the movie begins, and also not. But it was in doing that, that I realized that it also was the movie and should be in the movie and then it became the beginning. But I didn’t know it, when I was writing them, what I was doing exactly.

Kaitlin Fontana: Mm-hmm (affirmative) I find it interesting, when thinking about this film, I was trying to think about depictions of divorce in cinema, and of course it exists across film, but on this intensive scale, I could only really think of Kramer vs Kramer as a study of what it looks like when a marriage comes apart. There are obviously instances in other films, but I wonder if there were any touchstones for you culturally, either in film or elsewhere, that you looked at aside from your own experiences, or aside from the experiences of people around you that you know, that you thought, “Oh, there’s something to be learned from, or gleaned from, in terms of American divorce.” Which is a specific thing.

Noah Baumbach: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah, I was going to say Scenes from a Marriage, but that’s not an American… The movie, Shoot The Moon is also, I think, really great. Alan Parker movie with Albert Finney and Diane Keaton, and written by Bo Goldman too. It’s a great screenplay. For me, it was much more drawing from research. I’ve had to experience in divorce personally, but it was research, quite extensive research, that really helped me build the story and find the story, I think. I love those movies. I love Kramer. In a way, they’re already with me. I didn’t look at them again for this. It didn’t seem necessary in a sense. It was like they’ve done their things so well, I’m doing my thing, and they’re very much still with me, those movies, because they’re so good.

I’ve really, was looking at movies that were less thematically similar, or at least less obviously thematically similar, and often looking at them for blocking or color aspect ratio. Things that would maybe be more directorial, whereas the script, I think in the writing of the script, I was thinking less in terms of movies that have come before. Something might occur to me that I looked at while I was writing, but mostly what comes to mind now was more after I had the script and was moving towards interpreting it as a director.

Kaitlin Fontana: Right. Yeah, what does divorce look like depicted on screen, as opposed to what does it look like depicted on the page, I suppose.

Noah Baumbach: Right, and then things beyond divorce that all come out. There are all these other things of internal, external, new York and LA, which also have those kind of built into them. Portraiture, faces, because the movie’s got the internal and external of the outside world, but it also has the… Of our inside worlds, you see their faces, and portion of the movie where the lawyers take over, and in essence, take their voices away. So, there are a few sequences where we’re hearing a lot of people talking, but we’re actually just seeing their faces, and so I was thinking about portraiture in that sense, and also framing their relationship to each other in a room, and perspective, and things like that that were all… Because perspective’s a big part of the movie too, and this was something I thought a lot about in the script stage, which was when we’re with her, when we’re with him, when we’re with both of them, and we’re always with one or the other or both. We’re never with anybody else.

Everyone else is entering their narrative, and visually, when we approached this to, my visual interpretation of what I had written was to always keep the camera with them as well. So, we’re never over the shoulders of the lawyers while they’re talking to each other, we’re always over Charlie and Nicole’s shoulders. They’re watching these people talk, and that always keeps us with them as well.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah, the lawyers are an interesting gambit. I thought a lot about that too. Partly it’s because, obviously, these amazing performances. There’s an interesting sort of gendered aspect to it as well. There’s this light, airy office occupied by Laura Dern’s character that’s this feminine space of “Let’s talk it out.” And then there’s this cramped, dark, leather bound space of Ray Liotta’s office where he’s just like, “We’re doing this, we’re doing this, we’re doing this.” And you kind of feel this, to me it felt very like a gender tension of how the different sides of the legal system might, both, inform in a good way and a bad way how divorces can proceed. And I wonder when you were writing those characters, you talked about this a little bit just now, but I wonder what you wanted those characters to say about the entirety of the story.

Noah Baumbach: Yeah, well it helped for me knowing, for instance, that Laura Dern was going to play Nora Fanshaw in the movie, and a lot of those scenes came out of conversations I had with Laura about not only just life and relationships, but also about the character. There’s a monologue that she delivers later in the movie, and I wrote that in response to talking to Laura. We were talking about the character, and we both posited the question of why did she get into this in the first place? Because she’s so good at working within the system now, and her intentions aren’t totally clear in the movie. But Laura was saying, “I’ll bet when she started, at least, that she wanted to do good and to stand up for people who she felt were not being truly represented, and particularly women.” And so, when she was saying this, I thought, “Well, wouldn’t it be great if she returned to that at some point?” And so, it was in that dialogue that I came up with that speech that she delivers. If you asked me though, I went off on a tangent, but…

Kaitlin Fontana: No, that’s fine. I should have asked what your intentions were in writing these lawyer characters, and by the way, there’s also the Alan Alda lawyer, which is this other dimension too.

Noah Baumbach: Yeah, that’s interesting too, and his office, represented by a cat and wearing his associate/daughter’s glasses. Well, I thought a lot could be said about the divorce system in if you, and this is where casting says a lot as well, although the characters who are written very much in the way that you see them in the movie, but a shorthand, if you said to someone, “Well, you fire Alan Alda and you hire Ray Liotta.” You know what their needs and wants are now. And so that was, I thought with Charlie’s sort of journey with these different… The first lawyer, of course, Ray’s character says all these things that are very hard for Charlie to hear. They feel so aggressive. They’re insulting. It’s expensive. It’s everything you don’t want this process to be, and Alan’s character offers this wisdom and almost like a fatherly, gentle vibe, and it’s what you’re hoping is true. And Alan, I always thought that was interesting about Alan’s character when I was writing it was that he’s essentially right, but ineffective in this system, and Ray’s character in essence, all the things you didn’t want to hear, suddenly the system somehow seems to require now.

So, I thought much could be said in that way, and at the same time, it was an opportunity to write fun characters for actors and what was interesting about having the lawyers in this section of lawyers, it goes just the way you’re saying earlier about the ordinary or mundane, I wanted in every case, the lawyers to say how much they’re going to cost and to even later see Charlie write a check. Things that you would, in most movies, you would assume… You don’t even think about it but if you thought to think about it, you’d say, “I assume they paid them at some point.” I wanted to show that because of course, you were saying in the beginning, it is these very ordinary, but they become extraordinary in the context of what you’re going for there. They’re so big. How interesting to see somebody write a check for a lot of money that you can’t believe you’re writing.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah, and you know it’s coming out of his genius grant. It’s just this heart wrenching thing. Well, let’s pull back a little bit too, because I think we’ve been talking a lot in the minutiae, and the check writing, and I want to know your process when you’re like, “Okay, I’m going to write a film about divorce.” Where do you start? What’s your process as a writer when you sit down, “Okay, I’m writing this script now.” How do you start and what’s your process through to the rewrite phase?

Noah Baumbach: Well, I think, I didn’t set out so much that I’m going to write a divorce movie, I thought, “I’m going to write a love story but it’s going to take place in the narrative of the divorce.” And that is the accumulation of many different things, and research, and like I said, notebooks, and a few years of ideas. Including for instance, Adam sings Being Alive. That’s an idea, which I don’t know where it’s going to fit in and I don’t even know if it makes it into this movie, but this is something that I’d like to do in a movie at some point. So, some stuff is, “I like these ideas, maybe they come into this movie, maybe they don’t.” And other things are much more tailored specifically for the thing I really think I’m ready to write. But I think once I more consciously begin writing, when I feel like I see the fiction in essence, and particularly with this movie, because I was talking to so many people, and interviewing people who are telling me real stories. So, it has to become movie material in a way for me to really begin writing, I think.

It doesn’t mean I can’t write little scenes, or work stuff out, but once I really think I know what the script is, the way I tend to write, once I’m writing, once I’m in a final draft document and writing, is I write within the notes that I’ve taken. I’ll copy all… Because I write longhand often in notebooks, but then I’ll type them into a final draft document, so then I can start creating scenes within these things. Once I’m in some kind of linear fashion of a script, I tend to write, and I tend to edit the same way, which is I will keep moving forward and then I’ll go back and revise, and then I’ll move a little bit more forward and then I’ll go back and revise again. So, that by the time I’m at the end of the script, and that doesn’t mean I don’t have scenes that I know I’m going to arrive at later sort of written out, they’re just not part of it yet, but by the time I have a draft, and this basically works out the same way, by the time I have a cut of the movie, it’s much closer.

I don’t have a gangly, rough draft. It’s usually in pretty good shape, and then it’s a read over of that and maybe showing it to a few people. First people I’ll show things to, Greta, some friends, filmmaker friends, and people I might show it to first, and then my brother, and then it’s gathering those, hearing those responses, and then also my own experience of it now, then now I have this whole documents. So, then I’ll do a whole pass on the whole thing, and that’s say, it’s in that space where I came to that point of these scenes are extraneous that I had written. The scenes, like I said, about friends, or about going to school. It was in that, that I was felt, “Oh, I see now in a way I didn’t when I was working much more on the micro. Now I really see how they raise their hands.” It’s like, “You can get rid of us.”

Kaitlin Fontana: They start to stick out a little bit.

Noah Baumbach: A little bit.

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah.

Noah Baumbach: And then there might be some rearranging of things. There might be some feeling I need a bridge somewhere. The structure of Marriage Story also, it’s built around these fade outs, and those were all in the script, and there’s some time jump within each one too. So, part of it too is also understanding what happened in those breaks, in the three seconds, or whatever it is that, of the fadeout. So, how has that shifted where we are ahead of time? And so, looking at a draft of it, maybe I’ve included too much in a section and I can actually allude to stuff that maybe takes place, in essence, within the black or I haven’t put enough in. I’ve let too much time pass. That I need to dramatize some of that stuff too. So, that’s also where structure, I always find, is helpful. Structure helps me, you said, what you include and what you don’t and how you’re structuring, and in the case of this, because it does have these advances in time, and so you get to see how much has changed and how much hasn’t changed as we go through this process.

Kaitlin Fontana: So, in this particular case, how long of a process are we talking about? How long between when you gathered up those notes and said, “Okay, there’s fiction here and it’s time for me to make this into a script.” To when you were like, “Okay, this is the script.” What’s that span of time for you?

Noah Baumbach: I don’t remember exactly, but I would say roughly six months or something. But it’s that thing of an overnight sensation 10 years in the making. That sort of, it’s six months, but after I’ve had years of processing things.

Kaitlin Fontana: Mm-hmm (affirmative) and you’d mentioned, a little bit, this earlier, I found it a little inside baseball but handled well in the film, that there is this dichotomy of East coast, West coast that I think is very familiar to a lot of us on the inside of the industry. Writers, directors, actors, whatever, that there is this prevailing feeling, although it’s not leaned on too hard, that to be in the East, to be as Charlie’s a theater director and Nicole is an actor, and it’s this avant garde theater in that she sort of expresses this desire, and it’s a desire that she’s had for a long time, to be in LA. To be in television. To be in film, and that there is this feeling of tension between those two things and that perhaps one is more legitimate than the other. The East coast theater being higher minded and the West coast TV side being selling out, and I wonder what does that reflect for you, thematically, through these characters, and through this story?

Noah Baumbach: Well, I thought of the locations, of course there’s the specifics of it and I was always aware of preconceptions that insiders might already have, but even just a general audience might have about New York and LA we’ve seen versions of this, or jokes about. So, I wanted to both be aware of that and play on that, but also do something else because I felt like you have the specifics and you have the… But it’s really about a changing notion feeling of home, because these two locations become, once the lawyers get involved, they actually become chits and their weapons in battle, and suddenly even Charlie and Nicole are digging into the identity, their identity, with these places. Charlie says, “We are New York family.” And we hear Laura’s character, Nora, talking about how Nicole grew up in LA. This is very much where her mom is, and we also, because we’re with Nicole in LA earlier, we’re also seeing that home, and then we see her at the new home she creates, and Charlie tries to stage a home in a transitional home and I felt like, “Well, these sort of notions of home are all there.” And so, that New York and LA could both be the cities they are and also provide visual interest to.

I thought it’ll be fun to shoot those cities in contrast to each other because they are, as you say, they’re sort of linked, in this business, they’re linked to inextricably linked, but they’re so different. It’s radical how different they look. The light in Los Angeles is so different and the lifestyle is so different. So, that you have all that, but really what I felt I was able to present was these externalized ideas of what home is, or could be, when really these internalized ideas of home are what the story is actually redefining, and what the characters need to redefine as they go through this journey.

Kaitlin Fontana: So, with this story having been told the way it is, do you think you have anything else to say about love?

Noah Baumbach: You mean for the rest of my career?

Kaitlin Fontana: Yeah.

Noah Baumbach: Sure. Yes. I feel like there’s a lot of material out in the world.

Kaitlin Fontana: So, what’s next then? Are you able to take a second and think, or are you already off on the next notebook? The next set of things?

Noah Baumbach: The notebooks are all there, but I don’t know what’s next. This is the first time, I would say, in quite some time that I don’t know. Usually I have, when I’m finishing one movie, the next one starts to reveal itself some way, and that was the case at the end of the Meyerowitz stories. When I was finishing my last movie, this one seemed to suddenly become clearer to me, but that didn’t happen on this one. So, I’m both taking it as a, maybe, a positive sign, but also it’s unchartered territory for me.

Kaitlin Fontana: Wow. Well, good luck navigating it.

Noah Baumbach: Thank you.

Kaitlin Fontana: Thank you for being here.

Noah Baumbach: Thanks for having me.

Kaitlin Fontana: That’s it for this episode. OnWriting is a production of the writers Guild of America, East. Tech production and original music is by Stockboy Creative. You can learn more about the writers Guild of America, East online at wgaeast.org. You can follow the Guild on social media @WGAEast and you can follow me on Twitter at @KaitlinFontana. If you like this podcast, please subscribe and rate us. Thanks for tuning in. Write on.