101 Greatest Screenplays of the 21st Century (*so far)

Writers Guild of America, East (WGAE) and Writers Guild of America West (WGAW) members voted to determine WGA’s 101 Greatest Screenplays of the 21st Century (*so far).

Announced on December 6, 2021, the list’s noted writing credits are based on that date.

1. Get Out (2017)

Written by Jordan Peele

“I realized early in the writing that Get Out is so much more than simply what happens when you have a black male protagonist at the center of a horror film,” Peele told Written By. Get Out, which won the 2018 Writers Guild Award for Original Screenplay, made an impact that transcended genre. Its fantastical premise—a coterie of the privileged literally co-opting the bodies of the Black race—is darkly comedic, culturally explosive, and hauntingly historical all at once.

2. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004)

Written by Charlie Kauffman, Story by Charlie Kauffman & Michel Gondry & Pierre Bismuth

The germ of the idea came from conceptual artist Pierre Bismuth, via director Michel Gondry: What if you sent postcards to people informing them they’d been erased from someone’s memory? How would they react? Kaufman’s narrative, winner of the 2005 Writers Guild Award for Original Screenplay, is structurally ingenious in fashioning the story of romantic love and the evolution of a relationship as a metaphysical, tragic-comic journey about love, loss, time, and a memory-erasing company called Lacuna.

3. The Social Network (2010)

Written by Aaron Sorkin, Based upon the book Accidental Billionaire by Ben Mezrich

We begin the story of the decline of Western civilization with a Harvard sophomore who suffers from an acute case of logorrhea returning to his dorm room after a bad date. Blowing off steam with a light bit of hacking, he soon creates a platform to rate coeds called FaceMash. From there, Sorkin—with expert pacing and time shifts—turns the Facebook origin story into a taut courtroom (technically, depositions) drama, pitting the aforementioned outcast Mark Zuckerberg against twin Harvard jocks the Winklevoss twins. There are no heroes of the IP dispute in this screenplay, which won the Writers Guild Award for Adapted Screenplay. It is uncanny how prescient the portrayal of Zuckerberg feels today, however: After all, he’s referred to as an “asshole” in the very first scene.

4. Parasite (2019)

Screenplay by Bong Joon Ho and Han Jin Won, Story by Bong Joon Ho

In Bong’s dark satire, the yuppie Park family lives in architectural splendor in the hills about Seoul. The scrappy Kims fold pizza boxes in a subterranean apartment prone to flooding. When one of the Kims begins tutoring one of the Parks, the have-nots begin infiltrating the lives of the haves, exposing the porous insulation of privilege. The theme of income inequality is exposed throughout the plot like a Russian doll. In college, Bong tutored the children of a rich family in Seoul whose house had a private sauna on the second floor. The experience returned to him in writing the 2020 Writers Guild Award-winning original screenplay for Parasite.

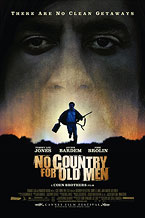

5. No Country for Old Men (2007)

Written for the Screen by Joel Coen & Ethan Coen, Based on the Novel by Cormac McCarthy

Set on the plains of West Texas, the Coens’ screenplay, winner of the Writers Guild Award for Adapted Screenplay, is a master class in the power of the unsaid on the page. In place of words are cryptic, existential musings and brief encounters that conclude with sudden bursts of violence. What is happening is a chase, as a rancher with stolen drug money stays a step ahead of a hit man with a bowl haircut and a cattle gun and a world-weary sheriff futilely trying to comprehend man’s inhumanity to man. It’s a plot that unfolds as if pre-ordained by a higher—or is it lower?—power.

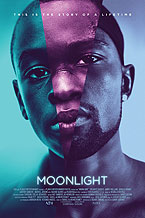

6. Moonlight (2016)

Screenplay by Barry Jenkins, Story by Tarell Alvin McCraney

Barry Jenkins’ 2017 Oscar- and Writers Guild Award-winning screenplay, divided into three equally compelling coming-of-age chapters in the life of a young Black man in Miami, is an adaptation of Tarell Alvin McCraney’s unpublished play In the Moonlight, Black Boys Look Blue.Jenkins and McCraney both grew up in the Liberty City neighborhood of Miami, raised by mothers who struggled with drug addiction. While adapting McCraney’s work, Jenkins told the podcast Script Apart, he realized how the screenplay would invariably be this “combined biography of myself and Tarell’s life.”

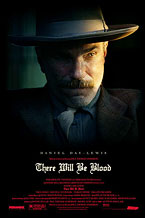

7. There Will Be Blood (2007)

Screenplay by Paul Thomas Anderson, Based on the Novel Oil! by Upton Sinclair

Anderson’s epic, turn-of-the-century, neo-historical tale of oil baron Daniel Plainview feels as essential to understanding the DNA of California as Robert Towne’s Chinatown. Anderson told interviewer Henry Rollins that he began writing There Will Be Blood partly “out of boredom,” taking passages from Upton Sinclair’s novel and re-crafting them as his own. From there, a screenplay “started to stick.” The wordless scenes that commence the film, with Plainview down a mineshaft, hacking away with a pickaxe, are neatly bookended by the film’s ending: Plainview, now rich and alone, hacking away at the head of his arch-nemesis, a preacher, with a pin from his personal bowling alley.

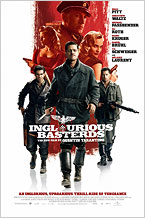

8. Inglourious Basterds (2009)

Written by Quentin Tarantino

Tarantino wrote the story years before revisiting it as a script, he told Filmmaker magazine. “I thought, Okay, maybe I could do it as a miniseries, but let me try to tame this, to make it into a movie.” Tarantino’s World War II characters, both Lt. Aldo Raine, leader of the “Basterds,” and Hans Landa, the chillingly decorous Nazi henchman, function well as ciphers for Tarantino’s fondness for scenes in which horrific violence is preceded by long, anecdotal tangents.

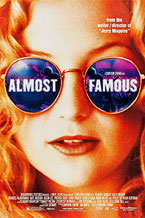

9. Almost Famous (2000)

Written by Cameron Crowe

The quintessential rock ’n’ roll coming-of-age film is based on Crowe’s experiences as a 17-year-old correspondent for Rolling Stone. In reliving his home and road life, Crowe captures both the times and his heady place in it with heartfelt aplomb. As Crowe told Empire magazine on the film’s 20th anniversary, the challenge was writing something that was “personal but not indulgent, and might catch what it felt like to be at the rock circus back then.”

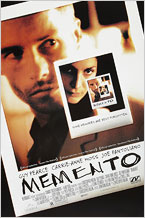

10. Memento (2000)

Screenplay by Christopher Nolan, Based on the Short Story by Jonathan Nolan

In an old YouTube video, Christopher Nolan stands at a chalkboard and diagrams the plot of his film for an interviewer. He explains where the “backward” narrative structure goes, alongside co-existing timelines told from objective and subjective points of view. Within this is the story of a man suffering from memory loss trying to solve the murder of his wife. Nolan told IndieWire that Graham Swift’s novel Waterland was an influence, and that he found conventional movie plot structure constraining, saying: “I’m trying to put together that narrative influence that I see used more freely in books.”

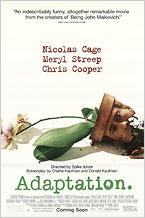

11. Adaptation (2002)

Screenplay by Charles Kaufman and Donald Kaufman, Based on the Book The Orchid Thief by Susan Orlean

Kaufman shared screenplay credit with his imaginary identical twin brother: Have we mentioned that Adaptation is a painfully funny illustration of writer’s block? In the script, the fake Kaufman brother pitches a serial killer script, while the “real” Kaufman is self-lampooned as a tortured artist spiraling over the problem of adapting Susan Orlean’s non-fiction book The Orchid Thief. Praising the sheer amount of ideas in the film, A.O. Scott of The New York Times called Adaptation “a movie about its own nonexistence—a narrative that confronts both the impossibility and the desperate necessity of storytelling.”

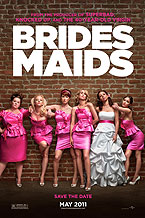

12. Bridesmaids (2011)

Written by Annie Mumolo & Kristen Wiig

At long last, Hollywood was inclined to believe that a studio comedy fronted by female characters who were not in active pursuit of a man and not trying desperately to have a baby could work. The screenplay, presumably minus the infamous bridal dress sequence, was based on the many weddings in which Mumolo participated. Mumolo and Wiig had discovered their chemistry as co-writers as sketch writer-performers with The Groundlings.

13. Brokeback Mountain (2005)

Screenplay by Larry McMurtry & Diana Ossana, Based on the Short Story by Annie Proulx

“They were raised on small, poor ranches in opposite corners of the state.” So begins Annie Proulx’s 1997 New Yorker short story, set in Montana, about modern-day cowboy lovers Jack Twist and Ennis del Mar. In an interview with the American Film Institute, co-screenwriter Diana Ossana—who, with Larry McMurtry, won the 2006 Writers Guild Award for Adapted Screenplay—recalled reading Proulx’s story in the middle of the night and again the next morning. She cried both times, and then showed the piece to McMurtry, suggesting they adapt it. “It’s the only time he’s agreed with me without an argument,” Ossana said. He said, ‘Sure.’”

14. The Royal Tennenbaums (2001)

Written by Wes Anderson & Owen Wilson

Three child prodigies; a father, Royal, devoted to dissipation; and a memoirist/archeologist mother, Etheline—these are the broken pieces of the family Tenenbaum. The movie, a kind of comic novel in the visual language of film, complete with omniscient narrator, “is keenly aware that divorce is a unique hurt, different from other types of loss because it doesn’t strike out of the blue,” writes Matt Stoller Zeitz in his book of essays, The Wes Anderson Collection.

15. Sideways (2004)

Screenplay by Alexander Payne & Jim Taylor, Based on the Novel by Rex Pickett

The story of two friends on a road trip through wine country is also an examination of the male ego in crisis. Miles is a broken-hearted unpublished novelist and wine connoisseur, Jack is a washed-up actor, living off the fumes of a career in daytime soaps. “Because we liked the novel so much, it was a struggle to keep the screenplay as short as possible,” Payne told Variety. Miles and Jack’s shenanigans—mostly Jack’s—crescendo in a decidedly offbeat act of male bondage. The Oscar- and 2005 Writers Guild Award-winning adapted screenplay comes to pack an emotional punch because the characters, and the friendship, are so believable.

16. Lady Bird (2017)

Written by Greta Gerwig

“I let all of these characters talk to me, and talk to each other. I overwrite,” Gerwig told Written By of the genesis of her screenplay for Lady Bird, about 17-year-old Sacramento Catholic schoolgirl Christine McPherson, aka “Lady Bird.” In addition to having arguably the best explanation ever for the presence of a nickname (“It was given to me, by me,” Lady Bird says), the screenplay’s highly affecting mother-daughter relationship begins with a classic deploying of “show don’t tell,” with Lady Bird exiting a moving car, stage right, during a fight with her mother.

17. Her (2013)

Written by Spike Jonze

“There’s definitely ways that technology brings us closer and ways that it makes us further apart—and that’s not what this movie is about,” Jonze told The New York Times about the film that won the 2014 Writers Guild Award for Original Screenplay. Theodore, divorced and lonely, works for a company called “Beautifulhandwrittenletters.com”—a ghostwriter of other people’s heartfelt feelings. Soon, he begins dating, and falling in love with, a new, intuitive operating system. “It really was about the way we relate to each other and long to connect: our inabilities to connect, fears of intimacy, all the stuff you bring up with any other human being,” Jonze said.

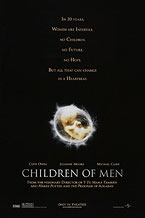

18. Children of Men (2006)

Screenplay by Alfonso Cuarón & Timothy J. Sexton and David Arata and Mark Fergus & Hawk Ostby, Based on the Novel The Children of Men by P.D. James

Some of the most celebrated shows in the so-called “bleak TV” era (The Handmaid’s Tale, The Leftovers, The Walking Dead) seem to owe a debt to Children of Men. Co-screenwriter Timothy Sexton told Colorado Public Radio that it was the post-9/11 zeitgeist that sparked the way into James’ 1992 dystopian novel set against mass infertility and the possible end of humanity. “Fertility is just a way to talk about crisis, and a way to talk about human hope,” Sexton said. “For me this is all kind of a post-9/11 phenomenon, where the West had this existential shock and began asking harder questions about where it’s all headed.”

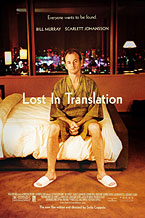

19. Lost in Translation (2003)

Written by Sofia Coppola

Arguably the best role ever written for Bill Murray, in terms of capturing his ineffable qualities—the goofball, the empath, the ironist. Coppola has said she based her 2004 Writers Guild Award-winning original screenplay on trips she took to Tokyo in her 20s. The age-inappropriate connection between Murray’s Bob Harris, an actor shooting a high-paying whiskey commercial, and Scarlett Johannsen’s Charlotte, a young woman stranded by her photographer husband, simmers with sadness. With their middle-of-the-night jet lag, it’s as if Bob and Charlotte have slipped into another dimension, guided by Coppola’s keen powers of observation.

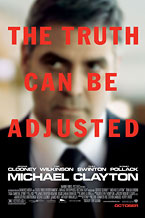

20. Michael Clayton (2007)

Written by Tony Gilroy

Gilroy proved that great legal thrillers needn’t take place in the courtroom. The titular character is a “fixer” at the white-shoe defense firm Kenner, Bach & Ledeen—a “janitor” sweeping others’ malfeasance under the rug. Until he isn’t. In 2020, reconsidering Michael Clayton for the website rogerebert.com, Roxana Hadadi concluded: “At a time when human lives are regularly diminished for corporate gains, the ferocious anger of Michael Clayton—the power of one person taking a stand—feels like a miracle.”

21. Little Miss Sunshine (2006)

Written by Michael Arndt

Arndt’s first produced screenplay won the 2007 Writers Guild Award for Original Screenplay and an Oscar. The Hoovers, a family on the waitlist for the American dream, head out from Albuquerque in their creaky VW bus. Destination: a child beauty pageant in California for eight-year-old, Olive. The JonBenét Ramsey story this isn’t. But then, the Hoovers are general disrupters of the tidy divide between the “beautiful” and the “ugly,” “winners” and “losers.” Arndt’s script, producer Ron Yerxa told The Hollywood Reporter, read “like a Ph.D. thesis on cultural emptiness in America.”

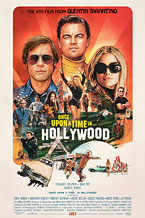

22. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019)

Written by Quentin Tarantino

Revisionist history doesn’t get more audacious and satisfying than the Manson family killers going to the wrong house on Cielo Drive and meeting their own spectacularly grisly fate. For all the biographical appearances, your Manson and Squeaky Fromme and Sharon Tate, it’s the fictitious cowboy actor Cliff Booth and stuntman sidekick Rick Dalton that most surpris, providing the script’s emotional resonance—not exactly a staple of Tarantino’s work. Their scenes, both together and apart, play like a paean to the “once upon a time” of the title.

23. Promising Young Woman (2020)

Written by Emerald Fennell

On the surface, Fennell’s 2021 Writers Guild Award-winning Original Screenplay is a kind of feminist riff on the Death Wish franchise: At bars, Cassandra feigns near-blackout drunkenness to lure and then punish “nice guy” predators who are one opportunity away from committing sexual assault. But Fennell told the Los Angeles Times that she wanted to write “a revenge journey a real woman might go on,” not one involving guns. “In what ways can we exercise power, threaten or terrify?” Fennell said. “Cassandra knows, because she is an expert at existential dread, partly because she is riven with it herself.”

24. Juno (2007)

Written by Diablo Cody

The jokes—“It’s probably just a food baby. Did you have a big lunch?”—mixed with the tender and the awkward catapulted Cody’s script to a Writers Guild Award for Original Screenplay. Christopher Orr of The Atlantic praised Juno for being “able to distinguish between a bad situation (being 16 years old and pregnant) and truly unhappy circumstances: Juno’s parents are disappointed but not disapproving; the Lorings, while not quite as they first appear, never slip into callous caricature; and Paulie Bleeker is everything, I imagine, you would want in the teenage father of your unintended child. Juno herself, moreover, wastes no time on self-pity.”

25. The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

Screenplay by Wes Anderson, Story by Wes Anderson & Hugo Guinness

The Austro-Hungarian Empire-infused Grand Budapest Hotel, winner of the 2013 Writers Guild Award for Original Screenplay, pays homage to both the interwar fiction of Stefan Zweig and the movies of the Marx Brothers. Far from needing no introduction, the characters all give off so much eccentric biography that introduction is what you want. There is Gustave H., the raffish, oh-so-dedicated concierge; his 84-year-old lover, the dowager Madame H.; Kovacs, her attorney; the “lobby boy” narrator Zero Moustafa. Etcetera. Guinness, Anderson’s co-writer, is an artist whose work hung on the walls of the Tennenbaum’s home.

26. The Dark Knight (2008)

Screenplay by Jonathan Nolan and Christopher Nolan, Story by Christopher Nolan & David S. Goyer, Based Upon Characters Appearing in Comic Books Published by DC Comics, Batman Created by Bob Kane

“Some men just want to watch the world burn.” More than summarizing the anarchic nature of the Joker, this observation by butler/confidant Alfred Pennyworth challenges the worldview of his employer, Bruce Wayne, aka Batman. It’s one thing for a superhero to fight crooks with rational agendas; it’s another to battle chaos created for its own sake. This dilemma drives the epic script that Christopher Nolan assembled with Jonathan Nolan and David S. Goyer for the second chapter of a blockbuster trilogy. Paralleling the Joker’s crime spree is competition for moral high ground between Batman and Gotham City’s DA, Harvey Dent: one man seeking change within the legal system, the other without. By the end of the dizzyingly paced ordeal the writers put these characters through, Batman and Harvey are victims of the Joker’s pointless malevolence—and the superhero genre has reached unprecedented levels of thematic ambition.

27. Arrival (2016)

Screenplay by Eric Heisserer, Based on the Story “Story of Your Life” Written by Ted Chiang

In the same way the aliens at the center of Arrival travel unimaginable distances to reach Earth, Eric Heisserer took a long journey bringing Ted Chiang’s “Story of Your Life” to the screen. First came the industry’s chilly reception to a heady narrative about linguistics and Fermat’s principle of least time (try unpacking that one during a pitch meeting). Next came years during which Heisserer built his professional standing. Thereafter commenced a lengthy development process with director Denis Villeneuve. By the time the project was realized, Heisserer had written close to 100 drafts. Yet perhaps that number is unsurprising, because Arrival surmounts myriad hurdles—complex scientific theories, a tricky nonlinear structure, scenes in which the protagonist methodically decodes aliens’ nonverbal communication. Guiding Heisserer’s work, he told Written By in 2017, was passion to replicate the way Chiang’s story “uplifted me and broke my heart at the same time.” Heisserer won the 2017 Writers Guild Award for Adapted Screenplay for Arrival.

28. Jojo Rabbit (2019)

Screenplay by Taika Waititi, Based on the Book Caging Skies by Christine Leunens

Springboarding from dramatic source material, Taika Waititi offers an irreverent take on World War II in Jojo Rabbit, audaciously presenting Hitler as a young boy’s idiotic imaginary friend. (Not since Mel Brooks has a satirist razzed the Führer so mercilessly.) Set in Germany circa 1945, Jojo Rabbit centers on ten-year-old Johannes “Jojo” Betzler, an enthusiastic Hitler Youth member who discovers his mother has provided sanctuary for a Jewish teenager. At first, Waititi unfurls his narrative like a whimsical fable, showing Jojo caught between nationalism and rebellion. Then tragedy sparks growth. Despite the inherent weight of its subject matter, Jojo Rabbit is so consistently funny and personal and strange that Waititi sidesteps most tropes associated with WWII stories—thereby affirming his belief that insouciance hits differently. Treating the subject earnestly “would be something we’ve seen 20 times before,” Waititi told Written By in 2019. “What’s the point in that?” Waititi won the 2020 Writers Guild Award for Adapted Screenplay for Jojo Rabbit.

29. Inside Out (2015)

Screenplay by Meg LeFauve, Original Story by Pete Docter and Ronnie Del Carmen

Originating with Pete Docter’s observations about the emotional life of his preteen daughter, Inside Out attempts nothing less than mapping the psychological makeup of a human being still in the process of being formed. Docter and Ronnie Del Carmen established the premise of five personified emotions working as a team to help young protagonist Riley navigate life. Then Meg LeFauve joined the process to help build a viable narrative, adding recollections from her youth. As LeFauve told IndieWire in 2016, “When Riley comes home and says, ‘You want me to be happy but I’m not,’ that’s what I wanted to say to my parents when I was eleven.’” This being a Pixar endeavor, Inside Out juxtaposes profundities with frenetic action and shrewd jokes—as when the emotion Sadness shares that “crying helps me slow down and obsess over the weight of life’s problems.”

30. The Departed (2006)

Screenplay by William Monahan, Based on the Motion Picture Infernal Affairs , Written by Alex Mak and Felix Chong

Journalist-turned-novelist-turned-screenwriter William Monahan won the gig to adapt a Hong Kong thriller into an American star vehicle by transposing the story to his native Boston, and the authenticity of his script’s local color—tethered, of course, to black humor, gruesome violence, twisted morality, and ruminations on class divisions—ensured that Monahan’s contributions didn’t get overshadowed by those of his megawatt collaborators (director Martin Scorsese, stars Leonardo Di Caprio, Matt Damon, and Jack Nicholson, producer Brad Pitt). The key, Monahan explained, was approaching the bruising story about a cop infiltrating the Irish mob as a character piece, elevating pulpy intrigue to brutal psychodrama. How brutal? Try bashing-someone’s-broken-arm-against-a-pool-table brutal. Add in copious F-bombs, outrageous trash talk, and a criminal-kingpin role tailored so Nicholson could personify a grotesque B-town riff on King Lear, and the outcome is an unforgiving crime saga with swagger to spare. Monahan won the 2007 Writers Guild Award for Adapted Screenplay for The Departed.

31. Spotlight (2015)

Written by Josh Singer & Tom McCarthy

Everything about the project was daunting—grim subject, massive scope, painstaking research. But after resisting overtures for months, Tom McCarthy signed on to direct a movie detailing how the Boston Globe’s investigative team spent six months uncovering a pedophile-priest scandal. McCarthy enlisted Josh Singer to write the script, and once Singer delineated the trajectory of the investigation, the duo talked to key real-life figures. That process persuaded McCarthy to cowrite. Pillorying the Catholic Church was never the focus. Rather, the aim was demonstrating the importance of serious journalism—and dramatizing the pressures of that work. In Spotlight, an impassioned reporter pleads with his bosses to publish ASAP, lest more children suffer; an experienced editor confesses that he missed a chance to pursue the story years earlier; and everyone on the reporting team recognizes that if they get even one detail wrong, the credibility of their whole investigation evaporates. Singer and McCarthy won the 2016 Writers Guild Award for Original Screenplay for Spotlight.

32. Whiplash (2014)

Written by Damien Chazelle

A blistering two-hander about the costs of pursuing greatness to the exclusion of everything else, Whiplash was drawn from Damien Chazelle’s experiences as a drummer in an elite jazz band during high school. The band’s conductor was a taskmaster, so even though Chazelle grew under the man’s tutelage, dysfunction reigned. Years later, Chazelle tapped his memories for Whiplash, which he initially filmed as a proof-of-concept short, the festival success of which unlocked financing for the feature version. Just as protagonist Andrew Neiman’s relentless practicing echoes the obsessiveness that nearly led Chazelle to pursue music professionally instead of cinema, antagonist Terence (“Not quite my tempo!”) Fletcher’s viciousness offers a hyperbolic riff on Chazelle’s (tor)mentor. Cruel, demeaning, manipulative, and physically violent, Fletcher is such a fiend that his behavior rises to the level of metaphor—he personifies the voice inside every artist’s head proclaiming that painful sacrifice is the only pathway to excellence.

33. Up (2009)

Screenplay by Bob Peterson, Pete Docter, Story by Pete Docter, Bob Peterson, Tom McCarthy

As a child, Pete Docter accidentally let go of a balloon that soon disappeared from view. “That feels very much like what life is,” he mused in 2009. “It’s fleeting.” Up forefronts aging and grief while telling an exhilarating story that celebrates human connection. In the film’s revered prologue, Carl Fredericksen grows old with and then loses his wife—encapsulating why, when the main story begins, he’s a curmudgeon. As a tribute to his late wife, Carl ties balloons to his house and flies away, unexpectedly bringing along a stowaway—optimistic youth Russell. As their journey progresses, each teaches the other life lessons. Like Carl, Docter shared his adventure. Bob Peterson helped develop the story, and because Docter and Peterson found inspiration in Tom McCarthy’s 2003 indie The Station Agent, they invited him for a consult that morphed into a three-month tenure helping Docter while Peterson was on another project.

34. Mean Girls (2004)

Screenplay by Tina Fey, Based on the Book Queen Bees and Wannabes by Rosalind Wiseman

While working as Saturday Night Live’s head writer, Tina Fey read Rosalind Wiseman’s Queen Bees and Wannabes—a nonfiction examination of aggressive behavior among teen girls—and pitched SNL producer Lorne Michaels on a movie version. Fey then recalled a period during high school when she judged others as a means of fortifying her self-esteem. Wiseman’s scholarship and Fey’s memories begat Mean Girls, in which adolescent outsider Cady Heron tussles with “The Plastics,” a status-minded clique led by vicious Regina George. Cady ditches real friends when she falls under Regina’s thrall, gets drunk on the power of living atop a high school’s caste system, and finally rediscovers integrity. As Fey told Parade in 2019, “the core of the story is to not lift yourself up by tearing someone else down.” Surrounding that core are offbeat characterizations, indelible gags (“Stop trying to make fetch happen!”), and breathless pacing.

35. WALL-E (2008)

Screenplay by Andrew Stanton, Jim Reardon, Original Story by Andrew Stanton, Pete Docter

The poetic storyline of WALL-E, Pixar’s love story/cautionary tale about a lonely robot on a futuristic Earth crammed with garbage, didn’t come easily. According to Andrew Stanton, the concept emerged during a lunch with cowriter Pete Docter and Pixar’s then-boss, John Lasseter. Gradually, Stanton and his collaborators generated additional ideas. WALL-E finds love with another robot. Humans, stuck traveling in space for decades, have become shapeless blobs whose primary interaction is with entertainment devices. WALL-E discovers a plant, suggesting a path toward reclaiming Earth from the ravages of unchecked consumerism. Throughout the process, Stanton strove for storytelling purity—which meant keeping dialogue to a minimum. Working with Jim Reardon, who supervised the movie’s storyboard team, Stanton crafted some of the most transcendent moments in the Pixar canon—wordless sequences of diligent little WALL-E going about his work until circumstances draw his curiosity and empathy to the surface.

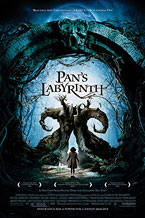

36. Pan’s Labyrinth (2006)

Written by Guillermo del Toro

“Every story has already been told,” Guillermo del Toro told a crowd at Comic-Con in 2011, “so the only variations I find are the voice of the storyteller and the context in which it’s told.” Inspired by literature, mythology, symbolism, and the dark wilderness that is del Toro’s imagination, Pan’s Labyrinth emerged directly from notebooks the filmmaker spent decades filling with drawings and text. The storyline also integrates visions from del Toro’s dreams, all of which helps explain how the writer-director conjured a blood-soaked parable about a young girl venturing from the harsh realities of Franco’s Spain circa 1944 into a surreal fantasyland where she might be the reincarnation of a princess. With its gruesome imagery, Pan’s Labyrinth is worlds removed from typical fantasy stories featuring children. Realizing his credo of using voice to create specificity, del Toro ventures into mystical thickets of emotion, terror, and wonderment.

37. Inception (2010)

Written by Christopher Nolan

Few modern endings linger as powerfully as that of Inception, a sci-fi epic about thieves invading victims’ dreams. In protagonist Dom Cobb, Christopher Nolan found a fresh take on the archetype of a criminal damaged by the moral ramifications of his work—Cobb is so adrift that he employs a spinning top to affirm when he’s in the real world, as opposed to the realm of dreams. This device allows Nolan to root Inception in Cobb’s journey even as the story sprawls to encompass audacious heists, mysteries within mysteries, and spectacular battles. Like Cobb focusing on his top, Nolan keeps the film’s uber-narrative charging forward while cityscapes morph like Escher drawings come to life, so once the script reaches its final beat—an image of the spinning top that leaves Cobb’s fate unknown—Nolan has formulated Inception as a provocative question. How do we know what’s real? Nolan won the 2011 Writers Guild Award for Original Screenplay for Inception.

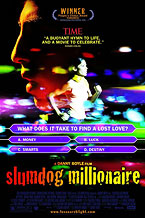

38. Slumdog Millionaire (2008)

Screenplay by Simon Beaufoy, Based on the Novel Q&A by Vikas Swarup

Faced with adapting Vikas Swarup’s episodic novel about an Indian teenager who wins big on a TV quiz show and gets accused of cheating, Simon Beaufoy faced massive challenges—beyond imposing a filmic structure, Beaufoy wanted a different emotional hook. “I just can’t get excited about money as a motivation in a film,” he remarked in 2009. Traveling to Mumbai for inspiration, Beaufoy visited the city’s slums and discovered hope, ingenuity, and joy amid the deprivation. This led the writer to lean into the source material’s notion of a young man who uses the internet to broaden his knowledge, to hinge the film’s narrative on a tender love story—and to conclude his script with a Bollywood-style musical number. Subtlety, Beaufoy reasoned, wasn’t the right approach for this milieu. “Nuance doesn’t stand a chance,” he said, “in the car-horn symphony of a Mumbai traffic jam.” Beaufoy won the 2009 Writers Guild Award for Adapted Screenplay for Slumdog Millionaire.

39. Before Sunset (2004)

Screenplay by Richard Linklater & Julie Delpy & Ethan Hawke, Story by Richard Linklater & Kim Krizan, Based on Characters Created by Richard Linklater & Kim Krizan

Perhaps no single line perfectly distills the iridescence of Before Sunset, the second film in a trilogy chronicling a romance across decades, but there’s a lot to unpack in this remark: “Memories are wonderful things if you don’t have to deal with the past.” Dealing with the past is part of what cowriter-director Richard Linklater, stars and cowriters Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke, and cowriter Kim Krizan do throughout Before Sunset, which reconnects Celine and Jesse nine years after Before Sunrise. Electrified by curiosity about what might have been, the onetime lovers scrutinize life choices past, present, and future. Designed to flow in real time and powered by torrents of pensive, playful, prickly dialogue, Before Sunset does more than merge the imaginations of its writers—the scriptuses the specificity of one couple’s journey to investigate the larger theme of how youthful romanticism changes when seen through adult eyes.

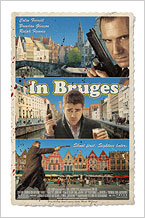

40. In Bruges (2008)

Written by Martin McDonagh

In Bruges opens with a murder inside a church and gets nervier with each successive scene. The tenebrous tale of two British hitmen on the lam in Belgium, In Bruges brazenly mixes farce with tragedy. The younger killer, Ray, despairs because he’s not yet numb to the immorality of his profession. His mentor, Ken, embraces beauty, whether it’s the stonework of ancient architecture or the prospect of helping Ray find redemption. The X factor in their adventure is crime boss Harry, who vacillates between compassion and sociopathy. Established as a brash playwright before venturing into film, McDonagh crafts moments that offend and shock and thrill all at once. Whether it’s a drug-fueled bacchanalia hosted by a crazed little person or a fateful subplot involving aggrieved Canadians, every element of In Bruges advances McDonagh’s fearless exploration of grief, rectitude, and transcendence.

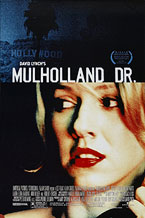

41. Mulholland Dr (2001)

Written by David Lynch

Arguably the apotheosis of David Lynch’s surreal style,Mulholland Dr. presents a seductive riddle that’s deliberately impossible to solve. Superficially, it’s the story of wannabe actress Betty trying to help sultry accident victim Rita recover her memory—until the WTF midpoint when the characters suddenly adopt different identities. There’s also a lurid crime narrative, a subplot involving a movie director, and, per the Lynch norm, a handful of sequences that are utterly unclassifiable. (Good luck trying to label a dream sequence in a movie that might be about a dream within a dream.) Even the story of how Mulholland Dr. got made is twisted. Lynch originally created the piece as a pilot for ABC, but after it got nixed for being too esoteric, he put together new financing, then wrote and lensed new scenes. In so doing, Lynch generated one of the most perplexing phantasmagorias in American cinematic history.

42. A Serious Man (2009)

Written by Joel Coen & Ethan Coen

In a 2009 interview, Ethan Coen described the approach that he and his brother, Joel, took while writing this darkly comic period piece about a professor who endures multiple crises. “The fun of the story for us,” Joel said, “was inventing new ways to torture [our protagonist] Larry.” Because A Serious Man explores how life tests its leading character’s faith, many have drawn parallels between Larry Gopnik and the Biblical figure of Job. Like Job, Larry suffers endless travails—an estranged wife, a son preoccupied with weed, a student scheming to avoid a failing grade. Also like Job, Larry seeks solace in religion, but that proves a source of consternation rather than comfort. (Among the Coens’ inspirations for this piece was an inscrutable rabbi they knew as children.) As the Coens relentlessly torment Larry, a cruel theme emerges—in some lives, misfortune presages oblivion, not salvation.

43. Amélie (2001)

Screenplay by Guillaume Laurant and Jean-Pierre Jeunet

This offbeat confection tracks the melancholy story of Amélie Poulain, a young Parisian woman striving to find the happiness that has evaded her since childhood. (In a prologue, a man leaps off the roof of the Notre-Dame cathedral and lands on Amélie’s mother, killing both.) Cowritten by director Jean-Pierre Jeunet and novelist/playwright Guillaume Laurant, the whimsical screenplay suggests we all have the power to reshape our worlds—or at least our worldviews—just as Amélie does. Thus, the title character is more than just an endearing gamine with a pixie cut. She’s force of will personified. After Jeunet initiated the writing process, he recruited Laurant, with the latter focusing on dialogue while the former concentrated on story structure and visuals. Together, they endowed bittersweet episodes with lucidity and momentum, positioning Amélie’s eventual victory as the gleaming conclusion of a magical-realism quest.

44. Toy Story

3 (2010)

### Screenplay by Michael Arndt, Story by John Lasseter, Andrew Stanton, and Lee Unkrich

Toy Story 3 defied expectations for threequels by adding a necessary beat to a beloved ongoing story, earning more than $1 billion worldwide, and giving countless viewers serious feels. The hook, which never changed throughout the years-long development process, was that Andy—owner of Woody, Buzz, and their pals—has aged in tandem with the years since Toy Story was released. In Toy Story 3, Andy must bequeath his playthings to someone new and thereby say goodbye to childhood. One of Michael Arndt’s goals was to convey the idea that although Woody and co. help guide Andy toward maturity, the choice to embrace change is ultimately Andy’s. Getting the nuances right took years and countless drafts; Arndt said one tricky sequence was rewritten 60 times. “Making one of these films is like building a cathedral,” Arndt told IndieWire in 2010. “It really is the expression of a whole creative community.”

45. The Favourite (2018)

Written by Deborah Davis and Tony McNamara

Twenty years before it reached the screen, The Favourite began as a first draft by aspiring screenwriter Deborah Davis, who extensively researched the story of two women who battled for position in the court of Queen Anne circa 1711. As Anne drifts into derangement, her friend and lover Sarah remains steadfast. Then Sarah unsuspectingly welcomes her ambitious cousin Abigail to Anne’s court, only to watch Abigail methodically usurp Sarah’s position. In the script’s bleak final scenes, however, it becomes clear that no one emerges from this conflict unscathed. Davis’s material caught the interest of director Yorgos Lanthimos, who hired TV veteran Tony McNamara for a rethink of the script; McNamara’s mandate included surfacing qualities that would resonate with contemporary audiences. The script wrought from Davis’s and McNamara’s combined sensibilities is a funny, poignant, and suspenseful examination of shifting dynamics between women.

46. Zodiac (2007)

Screenplay by James Vanderbilt, Based on the Book by Robert Graysmith

James Vanderbilt first read Robert Graysmith’s best-selling book about the Zodiac Killer when Vanderbilt was in high school, so by the time he met Graysmith in 2002, Vanderbilt had history with the material. The immersion showed in the 158-page script Vanderbilt wrote for producer Bradley J. Fischer, but an even deeper development process ensued once Vanderbilt and Fischer teamed with director David Fincher—the trio spent 18 months on interviews and research, culminating in Vanderbilt’s 200-page shooting script. Beyond evoking the fear that gripped 1960s NorCal during Zodiac’s crime spree, Vanderbilt’s script explores the real-life investigation by a cartoonist, a detective, and a reporter, all of whom suffer psychological wounds while trying to decode a murderer’s taunting ciphers. Dramatizing the peril of entering a monster’s secret world, the script ends where the real investigation did—without resolution—so the sense of lingering menace is palpable.

47. Gladiator (2000)

Screenplay by David Franzoni and John Logan and William Nicholson, Story by David Franzoni

Gladiator uses a huge canvas to tell a small story. “It is about a man just trying to get home,” David Franzoni said in 2020. For protagonist Maximus, however, getting home is complicated. Initially, he’s a revered soldier serving a noble emperor—but after a cycle of betrayals and murders, Maximus finds himself adrift, ostensibly lusting for vengeance but truly searching for a way to spend eternity with loved ones he lost. Franzoni, who first lit on the subject matter decades before becoming a professional screenwriter, pitched a historically accurate gladiator story to Steven Spielberg, who set up the project at DreamWorks. The concept enticed Ridley Scott to direct, at which point John Logan performed rewrites that moved deeper into fictionalization. William Nicholson then worked on the script during preproduction and filming. Issuing from this painstaking process was a script that imbues history with visceral immediacy.

48. The Incredibles (2004)

Written by Brad Bird

Both penned by Brad Bird, The Incredibles and its 2018 sequel are, to date, the only Pixar movies with solo writing credits. Influenced by Cold War-era pop culture that Bird consumed as a child, The Incredibles blends elements that shouldn’t mesh. Why is one of the most striking characters in this action story a fashion designer inspired by Edith Head? Why is this animated adventure predicated on a midlife crisis? How did blacklisting get in here? Bird combines notions that have fascinated him since childhood with mature themes, hence the challenges that super-parents Mr. Incredible and Elastigirl face while trying to balance family and work. The physical scope of the story is just as ambitious, because the script prescribed effects that CGI hadn’t mastered at the time preproduction began. “The first step to achieving the impossible,” Bird said in 2008, “is believing that the impossible can be achieved.”

49. Knives Out (2019)

Written by Rian Johnson

Simultaneously exemplifying and satirizing a narrative form is risky, but Rian Johnson does so with flair throughout this playful riff on whodunnits. By exploring the death of mystery writer Harlan Thrombey, a man connected to so many intrigues that all of his relatives are suspects, Johnson engineers enough misdirection to thrill any fan of Christie or Hitchcock. Woven into the puzzle is absurdity—a woman who vomits every time she tries to lie, a detective whose Southern accent is so thick a suspect refers to the investigation as “CSI: KFC,” a literal throne of knives at the crime scene. As Johnson explained, his goal was not to lampoon whodunnits but to refresh tropes—hence the choice to make Knives Out contemporary as opposed to a period piece. Johnson’s approach is sly rather than snarky, infusing a joyously twisted storyline with flamboyant characterizations, nervy jokes, and topical commentary.

50. Ex Machina (2015)

Written by Alex Garland

“We don’t understand how our cellphones and our laptops work,” Alex Garland told NPR in 2015, “but those things seem to understand a lot about us.” Long fascinated by society’s relationship with machines generally, and artificial intelligence specifically, Garland weaves a story around sentient robot Ava. Although what ensues is nominally a thriller, Ex Machina is fundamentally a meditation on consciousness. Evoking earlier thought exercises by Arthur C. Clarke, Stanley Kubrick, and Mary Shelley, as well as the work of futurists and philosophers, Garland asks whether AI is a threat, an evolution, an improvement—or all of the above. His script also puts forth the disquieting notion that mankind’s infatuation with technology long ago opened dangerous doors that can never be closed. Recall the full title of Shelley’s influential masterpiece—Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus—while considering how Garland’s script updates Shelley for the digital age.

51. Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (2014)

Written by Alejandro G. Iñárritu, Nicolás Giacobone, Alexander Dinelaris Jr. & Armando Bó

Fittingly for a script that blends farce, satire, tragedy, and a host of other narrative textures, Birdman hatched from a mélange of provocative ideas. Seeking a break from the angst of straightforward melodrama, cowriter-director Alejandro G. Iñárritu imagined an immersive one-take story about an actor suffering an existential crisis during the performance of a play. Despite initial resistance from collaborators Nicolás Giacobone, Alexander Dinelaris Jr., and Armando Bó—all of whom questioned the single-shot approach—Iñárritu sparked a lively collaborative process. What resulted was something bold, strange, and touching—a nervy rumination on how the compromises, disappointments, and exhilarations of an artistic career parallel the same patterns in life itself. Despite its intimate scale, the script is so thematically ambitious that the risk/reward ratio is breathtaking. “If you don’t do some things that terrify you,” Iñárritu told Variety in 2014, “I don’t think they’re worth doing.”

52. The Lives of Others (2006)

Written by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck

When he was a film student, Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck read about a conversation between Lenin and Gorky. “Lenin said he didn’t want to listen to his favorite piece of music anymore, Beethoven’s ‘Appassionata,’ because, he said, ‘If I listen to that music, it makes me want to stroke people’s heads and tell them nice things, but I have to smash in those heads without mercy to finish my revolution,’” von Donnersmarck told the Los Angeles Times. He immediately pictured a man with headphones on. “He thinks he’s going to listen to his enemy saying terrible things, and actually ends up listening to beautiful music. Within a couple of hours, I had the basic plot of the story.” As an East German Stasi agent listens in on the lives of two artists, the repercussions change them all irrevocably.

53. Nightcrawler (2014)

Written by Dan Gilroy

If it bleeds, it leads, and it led Dan Gilroy to create an amoral TV news stringer whose study of the business combines with his ambition to horrific, successful ends. As Gilroy said in Film Comment, the script clicked into place when he stopped trying to write a heroic lead and created an antihero instead. “What I found fascinating about the antihero is that he makes the world bend around him. He doesn’t change. He forces other characters to do things that they normally wouldn’t do…. They expose the world in a way that I don’t think you have the opportunity to do with heroes.”

54. 12 Years a Slave (2013)

Screenplay by John Ridley, Based on the book Twelve Years a Slave by Solomon Northup

In adapting Solomon Northup’s searing memoir of enslavement, John Ridley was challenged to find and develop “the moments in those twelve years that stand in the starkest relief,” he told Filmmaker Magazine. “You don’t want a film that is all pain and suffering, but at the same time, you don’t want a film that turns its head away from those difficult aspects of the storytelling.” No matter how brutal the story was, he used Northup’s faith to guide him.

55. The Big Short (2015)

Screenplay by Charles Randolph and Adam McKay, Based on the Book by Michael Lewis

Taking a book about the elements that coalesced into the 2008 financial crisis and turning it into a wild ride as well as an informative film, Charles Randolph and Adam McKay broke the fourth wall, helping the audience understand every twist of the economic screws. As McKay said to the crowd at a Writers Guild Foundation event, “The banks want you to believe this is so complicated. And it’s not. There’s just a massive disconnect in our culture between what we need to know and what we’re actually knowing.” They managed to make the terrible truth entertaining, and win the 2016 Writers Guild Award for Adapted Screenplay.

56. Moneyball (2011)

Screenplay by Steven Zaillian and Aaron Sorkin, Story by Stan Chervin, Based on the Book by Michael Lewis

In another great adaptation of another great Michael Lewis book, the use of statistical analysis to evaluate baseball players morphed into the compelling story of an underdog taking a swing against the system. The project endured a changing rotation of writers and directors for so long, everyone in Hollywood expected the film to flop. “The reason that this particular book was difficult to adapt is because you want to somehow recreate the experience of reading the book, which goes in and out of time, explanation of sabermetrics, and a lot of the historical context,” producer Rachel Horovitz noted in an interview with KQED. “It was a harder script to get down than most.” It took the screenwriting might of Steve Zaillian and Aaron Sorkin, working on separate drafts that were eventually combined, to hit Moneyball out of the park.

57. Black Panther (2018)

Written by Ryan Coogler & Joe Robert Cole, Based on the Marvel Comics by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby

Ryan Coogler and Joe Robert Cole knew the significance of the universe they were creating, with a Black superhero and a futuristic African utopia, untouched by colonial rule, that entered the words “Wakanda Forever” in the lexicon. But they started from an intimately personal perspective. “We worked from themes and philosophical questions as our base,” Ryan Coogler told Written By. “The big one was: ‘Am I my brother’s keeper? If I’m not related to you, am I responsible for you? Do I, as a Wakandan, have to worry about the rest of the world? And at what point do I stop worrying?’ It was like, if we can have characters who all have different answers to those questions, that will drive our story. That was how we talked about all the characters in the film.”

58. You Can Count on Me (2000)

Written by Kenneth Lonergan

Terry and his sister Sammy lost their parents at a young age, and it affected them both deeply in diametrically opposed ways: Sammy became as responsible as Terry is undependable. But their love and their history bonds them nonetheless, in this thoughtful look at messy family dynamics. Kenneth Lonergan told Charlie Rose, “I was really interested in the different strategies people use, or are forced into, to get through life, especially when they’re hit with some kind of tragedy, which these characters are.” With his ability to write painfully realistic dialogue, the gulf between what people say and what they mean has never been more pronounced than in this 2001 Writers Guild Award winner for Screenplay Written Directly for the Screen.

59. Boyhood (2014)

Written by Richard Linklater

Creating the story of a child growing up from age six to 18, Richard Linklater’s film takes on the unforced cadence of a boy’s life. “So many movies have a structure that’s built around satisfying plot, and leave no room, or very little, for these real moments,” Linklater said in Written By. “You hear all the time, ‘What are the stakes, what’s the payoff?’ That’s all artificial.…I thought, maybe I could do a whole movie without a plot. That doesn’t mean it doesn’t make sense. It’s plot that’s fake. What’s real is the way life unfolds, the way time moves, the way things don’t always pay off in big ways. Because they don’t. Your life doesn’t have a plot. It has character and story.”

60. Finding Nemo (2003)

Screenplay by Andrew Stanton, Bob Peterson, David Reynolds, Original Story by Andrew Stanton

For Andrew Stanton, the surprisingly moving animated tale of an overprotective clownfish searching for his missing son was rooted in his own experience as a father. Busy working on one movie after another at Pixar, Stanton felt he wasn’t seeing enough of his five-year-old son. “I made some daddy-son time to walk in the park, and I spent the whole walk going: ‘Don’t touch that,’ ‘Watch out for cars,’ ‘You’re going to poke your eye out,’” he told AP. “I sort of stopped myself and realized I was so afraid of something bad happening to him that I was missing out on the chance to connect with him.”

61. The Hurt Locker (2009)

Written by Mark Boal

This contemporary war movie centers on the members of an EOD (Explosive Ordnance Disposal) unit at work in war-torn Iraq. Screenwriter Mark Boal, formerly a journalist, embedded himself with a bomb squad to get a feel for their experience, and the results are evident onscreen in the characters’ naturalistic behavior. Boal said in Collider, “We were trying to make the dialogue feel spontaneous and lifelike, and the whole movie experience to feel tense and authentic and intense. And to do all that, you wanted it to feel kind of like you were parachuted into the war and not parachuted into a movie, so that was all very much our sort of goal for the script.” The film succeeds, throwing us into the action from the first nail-biting moment, and winning the 2010 Writers Guild Award for Original Screenplay.

62. Roma (2018)

Written by Alfonso Cuarón

Alfonso Cuarón never expected a film about his childhood, from the point of view of his family housekeeper (Libo in real life, Cleo onscreen), to strike such a nerve. “I was making a very specific film, about a very specific character, in the framework of a very specific family, in a very specific society, in a very specific country, in a very specific timeframe of history,” he noted in Written By. “Also, it’s in Spanish and Mixtec, it’s a drama in black and white, and it’s Mexican. It’s not like there’s a huge market for that kind of film.” After immersing himself in memories and extensive interviews with Libo, he wrote the script in three weeks, “without any consideration of structure, narrative, character arcs, or anything. Just letting it flow, coming from almost like a subconscious experience…and trusting that if a new memory arises, it is relevant.”

63. The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)

Screenplay by Terence Winter, Based on the Book by Jordan Belfort

In discussing the riotously unreliable narrator at the center of the film about Wall Street shenanigans, Terence Winter told David Erlich at MTV News, “Part of the fun and the charm of the book is in hearing Jordan’s voice, in hearing his take on things. Things that don’t necessarily lend themselves to dialogue, like him detailing the three different kinds of hookers, or the different stages of a quaalude high, those are just weird little observations.” He asked for director Martin Scorsese’s blessing to write the script with voiceover, “knowing that Goodfellas and Casino were written the same way, and to a certain extent Mean Streets as well. And so he said, ‘Yeah, let’s make this a companion piece to Goodfellas.’ So that was great that I had license to tell the story in that way.”

64. Hell or High Water (2016)

Written by Taylor Sheridan

“I like to wrap a socially aware film in a genre,” Taylor Sheridan told Written By, as he did with this story of two brothers who rob banks in order to save the family farm from, well, the bank, and the two Texas Rangers out to stop them. “I love playing with the idea of what we call genre films. Taking that genre and turning it on its ear, and turning it on its ear again. I don’t think of it as a Western, even though I was wildly influenced by Westerns. Is it a bank heist movie? Sure. Is it a buddy road flick? Sure. Is it a deep, dark family drama? Yeah. Is it a morality play? It’s all those things.” And despite its serious underpinnings, it’s also a hoot.

65. Manchester by the Sea (2016)

Written by Kenneth Lonergan

In another entry from Kenneth Lonergan, his protagonist suffers after making a mistake from which he can never recover, but must somehow come to accept. But the film isn’t simply bleak; as in real life, there is lightness and humor mixed in with the sorrow. “I’ve never seen there being a tremendous dividing line between comedy and tragedy,” Lonergan said to an audience at the New York Film Festival. “Even if it’s the worst of the worst, it’s not happening to everyone. It might just be happening to you, or to someone you know, while the rest of the world is going on doing things that are beautiful, or funny, or material, or practical.” With this script, he embraces it all without judgment.

66. A Separation (2011)

Written by Asghar Farhadi

This tense, riveting, morally complex film looks at two disparate and troubled Iranian families, the choices that decent people make out of fear, and the part that culture plays in it all. Writer Asghar Farhadi offers no easy solutions. He told The Guardian, “Today’s world needs more questions than answers. I’m not hiding the answers away from my viewers, I simply don’t know them. If you give an answer to your viewer, your film will simply finish in the movie theatre. But when you pose questions, your film actually begins after people watch it. In fact, your film will continue inside the viewer. The important thing is to think and give the viewer the opportunity to think. In Iran, more than anything else at the moment, we need the audience to think.” The result makes for haunting viewing.

67. Spirited Away (2001)

Written by Hayao Miyazaki

The animated Japanese fantasy drops ten-year-old protagonist Chihiro in a surreal spirit world, where she must survive and try to save her parents and return to the world of the living. As Hayao Miyazaki said in Midnight Eye, “It was through observing the daughter of a friend that I realized there were no films out there for her, no films that directly spoke to her. Certainly, girls like her see films that contain characters their age, but they can’t identify with them, because they are imaginary characters that don’t resemble them at all. With Spirited Away I wanted to say to them, ‘Don’t worry, it will be all right in the end, there will be something for you,’ not just in cinema, but also in everyday life. For that it was necessary to have a heroine who was an ordinary girl, not someone who could fly or do something impossible.”

68. Mad Max: Fury Road (2015)

Written by George Miller, Brendan McCarthy, Nico Lathouris

Some films have great chase sequences. This long-awaited entry to the Mad Max franchise IS a great chase sequence, one that was blocked out on over 3,500 storyboard panels. Co-writer George Miller said in the Hollywood Reporter, “The approach to this film, once the world is decided on, is almost like a documentary.…We had to make everything about it—the internal logic of everything you see in the movie, not only the objects and the cars and so on, but even the language—have the same cohesive logic as if you went into some anthropological film and saw a culture that we’re unfamiliar with. You see things that you don’t quite understand, but you know it has meaning to the people in the film.”

69. Booksmart (2019)

Written by Emily Halpern & Sarah Haskins and Susanna Fogel and Katie Silberman

Two teenage overachievers realize they’ve wasted their youth on schoolwork, and decide to have one epic night before graduation, in classic buddy-movie tradition. And this time, in a delightful update to the genre, the buddies are girls. Booksmart itself collected accolades while it sat on the shelf for a decade, and underwent several iterations, before co-writer Katie Silberman’s draft got the greenlight. She didn’t have to go far for inspiration. “I was a real Molly in high school,” she admits in Indiewire, naming one of the uptight protagonists. “I convinced myself it was because I was doing the responsible thing. Then I got to college and saw all the kids who I thought were just partying in more advanced classes than I was. I was like, ‘Wait a second, what have I done?’ In a lot of ways I pitched a story that was wish fulfillment for me.”

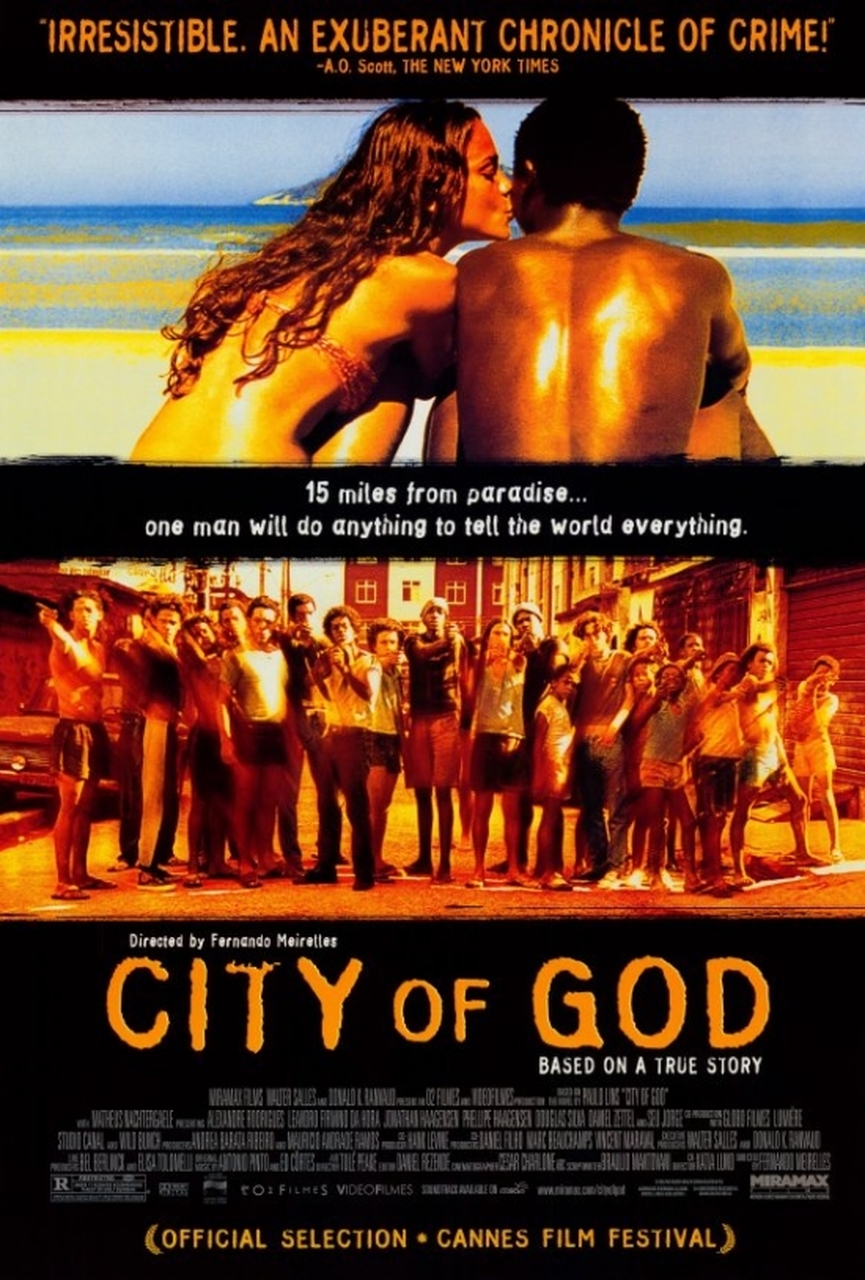

70. City of God (2002)

Screenplay by Bráulio Mantovani, Based on the Novel by Paulo Lins

The favelas (slums) of Rio are lightyears away from the glittering city they overlook. Areas like Cidade de Deus (City of God) have been abandoned to criminal gangs and corrupt officials, and life is lawless and brutal—but also filled with music and exuberant joy. Bráulio Mantovani adapted the novel by Paulo Lins, who had grown up in City of God. The film was shot using non-actors who had been trained in workshops for months before filming. “Each scene was rehearsed numerous times during the workshop period,” co-director Fernando Meirelles told the Irish Times. “Each time phrases were added or cut out, reactions or jokes were incorporated, and intentions sharpened. These contributions were passed on to the screenwriter, Bráulio Mantovani, and the script began to grow and grow.” The resulting film brought a naturalistic, colorful, heightened sense of the favelas’ bonds and violence to a shocked international audience.

71. Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018)

Screenplay by Phil Lord and Rodney Rothman, Story by Phil Lord, Based on the Marvel Comics

Superheroes take many forms, and endure many reboots, but this was one of the most inventive, as Spider-Man comes back into animated life—in parallel universes—with young Miles Morales at the helm. It didn’t come easily. As co-writer Phil Lord shared on a Twitter thread, accompanying photos of whiteboards, “We did a big shakeup of the story less than a year from release and we had to figure out how to reshape sequences we had already boarded and animated and fold them in with new stuff. Oh and we rebroke the whole third act. These dumb whiteboards became our bible. It’s less of an outline and more of a triage docket of what we were going to do to each sequence. It made sense basically to no one but us.”

72. Inside Llewyn Davis (2013)

Written by Joel Coen & Ethan Coen

Llewyn Davis is a sad sack of a folk musician, working his way down the ladder of success in the ‘60s. “It’s more interesting for me as an audience member to see a movie about a loser,” co-writer Ethan Coen told the Guardian. “Who wants to make a movie about Elvis, you know? We wanted a nice dick. We wanted that tension: kind of is, kind of isn’t, kind of is.” Added Joel Coen, “He’s the guy who blows his top or speaks out of turn or says something really dickish, but then, three minutes later thinks to himself: I’m a dick for doing that. Some dicks are just not self-aware.”

73. The King’s Speech (2010)

Screenplay by David Seidler

Prince Albert was horrified to find greatness thrust upon him when his brother, King Edward, abdicated the throne. A gentle man with a profound stutter, he was unprepared for the role of King, but he had no choice in the matter. Writer David Seidler was first drawn to King George VI as a child, because he suffered with a stutter as well. But the true story had long been repressed, so research was difficult, he explained in the Los Angeles Times. “It’s an embarrassment, and it’s swept under the carpet—even today, but much, much more then.” He even wrote to the Queen Mother to ask permission to write the script, “and she wrote back, ‘Please, not in my lifetime. The memory of those events is still too painful.’ And when the Queen Mum says to an Englishman, ‘Wait,’ an Englishman waits. I didn’t figure I’d have to wait this long.”

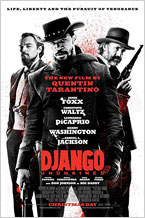

74. Django Unchained (2012)

Written by Quentin Tarantino

The Western, Southern, revenge fantasy follows an enslaved man as he frees himself and his family, wreaking fiery havoc on all oppressors. “I wanted to tell the story as a genre movie, as an exciting adventure,” writer Quentin Tarantino told Terry Gross on Fresh Air. “I like the idea of taking stories that oftentimes, if played out in the way that they’re normally played out, just end up becoming soul-deadening, because you’re just watching victimization all the time.” With his approach, the victim becomes the action hero on an Odyssean journey, with “the grand opera stage it deserves.” With operatic levels of violence, naturally.

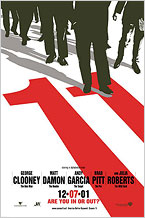

75. Ocean’s Eleven (2001)

Screenplay by Ted Griffin, Based on a Screenplay by Harry Brown and Charles Lederer and a Story by George Clayton Johnson & Jack Golden Russell

Writer Ted Griffin made a startling admission to Free Film University: “I don’t like the original Ocean’s Eleven. It may be iconic but it’s not good, as fascinating as the Rat Pack is to watch. But I liked those types of movies growing up—groups on a mission, like Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape, and The Professionals—and always wanted to do one.” His insouciant thieves are a charming, deceitful bunch as they design and pull off their Las Vegas caper. “The tricky part of writing Ocean’s was the Eleven part—making all eleven vital to the heist, with their own special skills and ‘moment in the sun,’ while also differentiating them.”

76. The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001)

Screenplay by Fran Walsh & Philippa Boyens & Peter Jackson, Based on the Book The Fellowship of the Ring by J.R.R. Tolkien

In discussion with Looking Closer, co-writer Peter Jackson was as interested in Tolkien’s inspiration as his writing, when it came to recreating that fantastic world onscreen. “He was just a guy who was profoundly irritated by things and annoyed, and he vented through this book that he created. And most of the things that he was irritated about are very reasonable things to be angry about,” including the destructive effects of the Industrial Revolution on his beloved English countryside, represented by the Shire and the Ring. “We actually tried to honor all that stuff. We made a real decision at the beginning that we weren’t going to introduce any new themes of our own into The Lord of the Rings films. We wanted to make a film that was based on what Tolkien was passionate about.”

77. Shaun of the Dead (2004)

Written by Simon Pegg and Edgar Wright

This shaggy zombie comedy doesn’t shy away from the horror it creates, and the combination is irresistible. Writers Simon Pegg and Edgar Wright were obsessed with George Romero’s Dawn of the Dead. As Wright said in the Guardian, “One evening, I was round at Simon and his pal Nick Frost’s flat for drinks when I said we should make our own zombie movie, a horror comedy. It would be from the point of view of two bit-players, two idiots who were the last to know what was going on, after waking up hungover on a Sunday morning.” Pegg and Frost went on to become those two idiots.

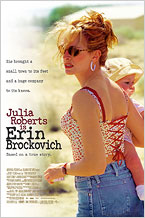

78. Erin Brockovich (2000)

Written by Susannah Grant

The moment screenwriter Susannah Grant first learned about Erin Brockovich, she knew she wanted to tell her story. It wasn’t just true, it was good: a twice-divorced single mother exposed and helped bring to justice Pacific Gas and Electric Company for poisoning the town of Hinkley, California’s water supply and covering it up. Grant summoned her own inner Brockovich, calling the producer with the story’s rights every couple weeks for months until finally scoring a meeting with Brockovich, who personally tapped her to tell the tale. “Let me tell you,” she explained in a 2000 keynote speech for the Academy Nicholl Fellowship in screenwriting, “if you think turning a script into a studio is nerve-wracking, try turning it in to the person on whom [it’s] based.”

79. Call Me by Your Name (2017)

Screenplay by James Ivory, Based on the Novel by André Aciman

In a list crowded with scripting elites, James Ivory stands alone—the only one of the lot to become half the namesake for an entire new genre of indie period dramas (along with longtime partner Ismail Merchant, Howards End, A Room with a View). At age 89, he earned an Oscar and 2018 Writers Guild Award for Adapted Screenplay for Call Me by Your Name, the youthfully romantic story of an American grad student in 1980s Italy, who falls for his professor’s 17-year-old son. “A lot of great stories and books aren’t written all that great,” deadpanned Ivory in a chat with the WGAW website about the film. “It’s everything about the story that’s great.”

80. Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (2017)

Written by Martin McDonagh

Whisky, cursing, and the truth are central to British playwright Martin McDonagh’s stage and screen work. Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, has them all in spades. He wrote the script for his ideal muse, Francis McDormand, who owns her role as a fire-starting, expletive-spitting mother who refuses to allow the case of her daughter’s rape and murder go unsolved. The film garnered McDonagh a Golden Globe for Best Screenplay, but he remained undiluted by such accolades: “F*K that Robert McKee shit,” he pronounced, in an interview with the Berlin Film Journal about how he writes. “I have a sense that something needs to happen at certain times, otherwise it’s not going to be an entertaining story, but there are no rules to be followed.”

81. The Lobster (2015)

Written by Yorgos Lanthimos and Efthymis Filippou

If you ever imagined what would happen if Paddy Chayefsky’s 1955 classic Marty was reimagined by George Orwell and punched up by Judd Apatow, The Lobster would get you pretty damn close to the answer. Yorgos Lanthimos and Efthymis Filippou’s script manages to be weird, dark, and funny, but still moving. It plumbs the absurdity of human behavior and allegorizes—to brutal extremes—the immense societal pressure placed on being in a relationship. Call it Squid Game for lonely hearts.

82. The Prestige (2006)

Screenplay by Jonathan Nolan and Christopher Nolan, Based on the Novel by Christopher Priest

In this dexterous Nolan brothers’ screenplay, two magicians in Edwardian London are driven into a dark rivalry over their shared obsession with creating the ultimate illusion. Adding to the pleasures of this script, the Nolans included Nikola Tesla from the source novel as a period-accurate player in the drama. Unlike the fictional pair of illusionists, the collaborative brothers say it’s trust that allows them to concoct great scripts. Speaking with the WGAW website, Christopher Nolan explained, “We trust each other, and that’s very good for the writing.”

83. Midnight in Paris (2011)

Written by Woody Allen

Woody Allen racked up his sixth Writers Guild Award and third Original Screenplay Oscar—more than anyone in history—in an entirely Woody Allen way; with a story that would be many screenwriters’ fantasy. Gil Pender is a disillusioned scripter who, while on a visit to Paris, gets spirited back to the 1920s to hobnob with the likes of Cole Porter, Ernest Hemingway, and Gertrude Stein. Nice work if you can get it. To top it off, Allen told The Hollywood Reporter that he didn’t have to do any research for the film: “Characters like Hemingway, Picasso, Salvador Dalí—they are so vivid and have such pronounced styles, I didn’t have to do any research at all. I could write it off the top of my head.”

84. The Master (2012)

Written by Paul Thomas Anderson

No modern writer-director has an oeuvre as pointedly divergent, eclectic, and successful as Paul Thomas Anderson, who seems, at each new turn, to be making the point that, no matter the trappings, the same themes of human existence reign. His films cover such disparate realms as the porn industry’s San Fernando Valley heyday in 1970s-’80s (Boogie Nights) to the buttoned-down life of an haute couture dressmaker in 1950s London (Phantom Thread). Perhaps his most esoteric, The Master, is about a struggling WWII vet who finds a sort of refuge with an L. Ron Hubbard-esque cult leader, Lancaster Dodd. Anderson told the L.A. Times in 2018 The Master was likely to remain his personal favorite of all his films. “I’m not sure it’s entirely successful,” he said, “but that’s fine with me. It feels right. It feels unique to me.”

85. Argo (2012)

Screenplay by Chris Terrio, Based on a selection from The Master of Disguise by Antonio J. Mendez and the

### Wired Magazine

### Article “The Great Escape” by Joshuah Bearman

Its Oscar win for Best Picture might have overshadowed the strength of this script, which took home both the 2013 Writers Guild Award and Oscar for Adapted Screenplay. Chris Terrio’s script is a marvel of narrative construction, drawing from multiple source texts as well as historical facts to recount how CIA operative Tony Mendez was able to rescue six U.S. diplomats during the Iranian hostage crisis using the ruse that they were part of a Canadian film crew making a science fiction movie. In another notch for truth over fiction, the scheme worked.

86. Y tu mamá también (2001)

Written by Carlos Cuarón & Alfonso Cuarón

Part road trip, teen movie, erotica, and art film, Y tu mamá tambiénchanged everything for Alfonso Cuarón, his brother Carlos, and Mexican cinema, which it helped reemerge after decades in the shadows. The logline may be simple—two horny teenage boys go on road trip with a beautiful older woman—but the film is not. The boys, Tenoch and Julio, learn things about themselves and each other in their time with Luisa that go well beyond anything either of them thought they were after.

87. Phantom Thread (2017)

Written by Paul Thomas Anderson

Paul Thomas Anderson knows his way around a taut, slow narrative burn, but none are more retrained and razor sharp than Phantom Thread, which stars Daniel Day-Lewis as fastidiously controlling dressmaker par excellence, Reynolds Woodcock, in post-war London. The slow unraveling of Woodcock is the meticulous deconstruction of love and art itself. So powerful an experience, Day-Lewis retired from acting after its completion. “Before making the film, I didn’t know I was going to stop acting,” Day-Lewis told W Magazine. “I do know that Paul [Thomas Anderson] and I laughed a lot before we made the movie. And then we stopped laughing because we were both overwhelmed by a sense of sadness. That took us by surprise: We didn’t realize what we had given birth to. It was hard to live with. And still is.”

88. Superbad (2007)

Written by Seth Rogen & Evan Goldberg

Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg started writing Superbad when they were still living it—as 13-year-old 12th graders at Pointy Grey Secondary School in Vancouver, Canada in the ‘90s. Years later, under the tutelage of comedy-Yoda Judd Apatow, Rogen learned how to make their script actually work. Rogen told the WGAW website how Apatow explained his philosophy for writing a story, which was to start first, “from an emotional thing that you’ve experienced, not even worrying about if it’s funny, and building the whole story on that.”

89. Little Women (2019)

Screenplay by Greta Gerwig, Based on the Novel by Louisa May Alcott

Louisa May Alcott’s iconic novel Little Women is so beloved it’s been adapted no less than seven times. The seventh go fell, with great results, to actress, writer, and director, Greta Gerwig. She did an ingenious thing no one else had before, incorporating the actual writing of the novel into her adaptation, with Jo March, one of the four sisters the novel centers on, as the author in place of Alcott. “I don’t remember a time when I didn’t know who Jo March was,” Gerwig told NPR. “She’s always been with me. So in some ways, it’s hard to know whether I was like Jo March, which is why I loved her, or Jo March molded me because I was trying to make myself like her.”

90. BlacKKKlansman (2018)

Written by Charlie Wachtel & David Rabinowitz and Kevin Willmott & Spike Lee, Based on the Book by Ron Stallworth

Charlie Wachtel and David Rabinowitz were next to nowhere as screenwriters when they stumbled across a copy of memoir titled Black Klansman by Ron Stallworth, via Police and Fire Publishing. Stallworth was the first Black detective to join the Colorado Springs Police Department, but that wasn’t the part of his story that made both writers immediately say, “this should be a movie!” In what seems more like a Key & Peele skit than real life, the book recounted how Stallworth infiltrated the Ku Klux Klan for nearly a year, even earning a membership certificate sent by none other than Grand Wizard David Duke. The story made for Spike Lee’s best movie in years, winning multiple accolades, including an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay for Wachtel and Rabinowitz.

91. The Farewell (2019)

Written by Lulu Wang

Though Lulu Wang had already written and directed her first feature, Posthumous in 2014, it was NPR’s This American Life that proved her big break when, in 2016, she wrote and narrated the autobiographical story titled “What You Don’t Know.” It recounted in fine detail how her family, who had moved to the States from China when she was 6, returned to China after her Nai Nai (paternal Grandmother) was diagnosed with terminal cancer. The family agreed to not inform the beloved 80-year-old of her diagnosis. Though she had previously shopped a more fictionalized version of the film with no success, the true version from the NPR essay drew multiple development offers. The resulting film, The Farewell, won critical laurels and dozens of awards.

92. La La Land (2016)

Written by Damien Chazelle

Damien Chazelle’s debut feature Whiplash put him on the map,butLa La Landwas the film he first wrote and dreamed of making. After meeting rejection everywhere, he wrote Whiplash as an easier film to sell on an indie budget. When it was a hit and he was flush with newfound clout, he was able to finally sell his musical about a purist jazz musician and a struggling actress who find love, and then lose it in Tinseltown. Chazelle told the WGAW website he didn’t know how much he related to the story until it was done: “I don’t know what it’s like to burst onto song on the highway or float up into the stars, but I do know intimately what it’s like to be a young wannabe artist in L.A., trying to reconcile big dreams with the reality of life in the city, trying to balance life and art and all the rejections, and the various little heartbreaks that L.A. can easily provide.”

93. Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan (2006)

Screenplay by Sacha Baron Cohen & Anthony Hines & Peter Baynham & Dan Mazer, Story by Sacha Baron Cohen & Peter Baynham & Anthony Hines & Todd Phillips, Based on a Character Created by Sacha Baron Cohen

Some eyebrows, and possibly a few bushy mustaches, might have been raised when the WGA nominated this first-of-its-kind reality-meets-mockumentary for Adapted Screenplay back in 2006. But time has been a friend to Borat, and the surprisingly intricate script behind it—proving them more prescient, incisive, and meticulously crafted than even its appreciators at the time knew. “We’d sit around the writers’ room and imagine the scene,” Sacha Baron Cohen said at a Writers Guild Q&A event in 2007. “’What do we want it to look like?’ Looking at the script and the finished film, they’re remarkably the same.”

94. The 40-Year-Old Virgin (2005)

Written by Judd Apatow & Steve Carell